Grassroots activism can sound like a vague notion at first, but the term becomes more concrete when we look at real-world examples.

Grassroots activism has played an important part in shaping human history, and the term could apply to movements going back thousands of years. Modern era examples include South Korea’s Candlelight Revolution, the United Farm Workers movement, the peace movement, and the Anti-Nazi boycott before World War II.

Most social movements either rely on grassroots activism entirely or at least in part. While most likely think of the term as being a modern concept, these types of actions were carried out in ancient history as well.

Research has shown that children of activists are more likely to engage in similar social actions when they are adults. Grassroots activism, then, can have profound impacts on current social dynamics and make it more likely that the next generation will build upon the results.

Grassroots movements are complex phenomena and not all have positive impacts on society – regardless of intentions. History shows that movements are most successful when driven by local communities; though, grassroots solidarity from non-local actors can be beneficial when done in concert with local organizing.

Public opinion around these issues can change dramatically over time. Some movements start as controversial and later become accepted by society. Other movements may come to represent the dominant views in society and later become controversial.

Grassroots activism also takes on many different forms. Some movements remain unstructured, while others are led by central organizers. Some campaigns are focused on an institutional change through legal reforms like treaties or even new governments, while others seek to improve social well being or provide services.

To understand these movements better, this post examines nine important case studies of grassroots activism stretching from the present day to as far back as the 10th century. These examples demonstrate the complexities around social action and how movements have achieved victory often against great odds. Some of these movements also show how the work of a few activists can sow the seeds for change that sometimes take root centuries later.

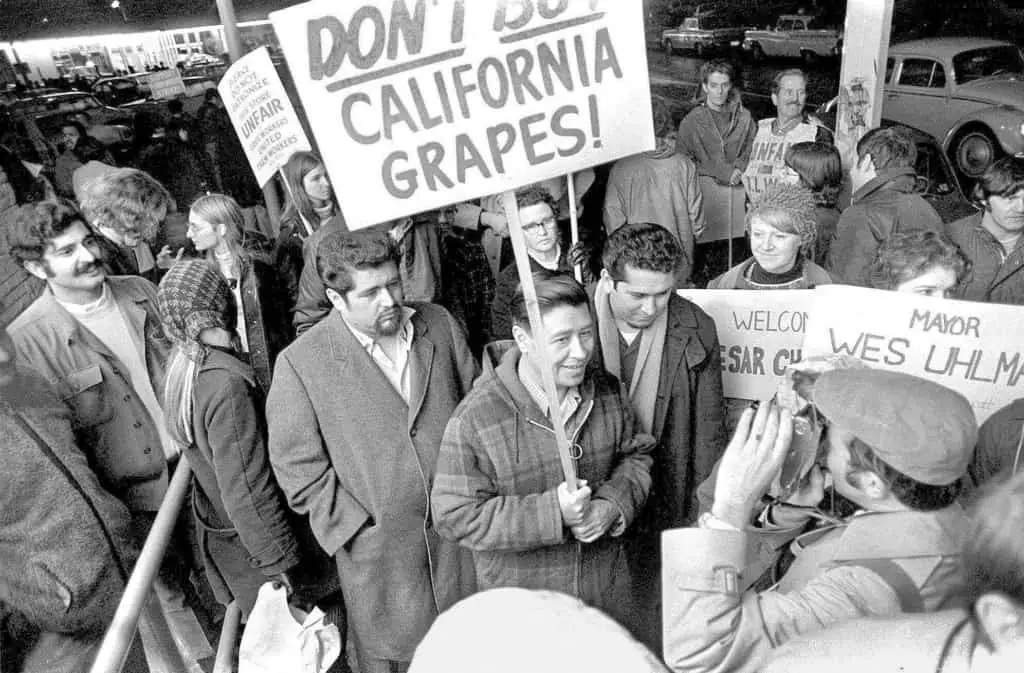

1) United Farm Workers Movement | 1962 – Present

The United Farm Workers (UFW) is a union that grew out of several grassroots organizations dedicated to protecting the rights of laborers and migrant workers employed in agriculture. The UFW is an oft-cited example among activists due to its success and near textbook execution of grassroots strategies.

Conditions for farmworkers in the 1950s and 1960s were often discriminatory and the jobs offered meager wages with poor conditions. In 1960, farmworkers were making an average of $0.90 per hour ($7.87 per hour in 2020 dollars). State laws regarding labor rights were often disregarded. Workers were temporarily housed in inadequate conditions which, in many cases, amounted to metal shacks with no indoor plumbing or cooking equipment. In the field, workers had even worse conditions. No ranches had field toilets at the time and some even charged laborers $0.25 per cup of water.

These conditions were nothing new and farm workers had been exploited particularly in California for more than a century. Agriculture industrial giants held tremendous sway over lawmakers and law enforcement. Circumstances seemed quite impossible for farm laborers at the time as many previous efforts to secure better wages and conditions failed. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, several organizations formed bringing skilled leadership and an energized grassroots base.

One organization called the Agricultural Workers Association (AWA) was led by Dolores Huerta. AWA later evolved into the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) which was a committee within the AFL-CIO. Around the same time that AWOC formed, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). Chavez had previously made a name for himself within the Community Service Organization (CSO) but left the group after it refused to put in any effort toward organizing farmworkers.

Starting in 1965, a series of strikes and collective actions gained workers several minor victories. The first two strikes in particular helped solidify a grassroots base, build popular support, create important partnerships, and ultimately achieve success for the movement.

During the first strike, the NFWA helped organize laborers at a rose farm. The laborers refused to work and secured higher wages only a few days later. Shortly after, the AWOC organized a strike for grape pickers in Coachella, California who were also seeking higher wages.

During the strike, thousands of Filipino and Mexican workers refused to harvest grapes until they received the same wages as domestic workers. Given that the harvest time for grapes is short, the grape owners had no choice but to pay the Filipino and Mexican workers at the same rates as domestic workers after 10 days of the strike.

While the strike worked in Coachella, other grape pickers faced the same issues and soon the movement began trailing north coinciding with the grape harvest. Grape owners began bringing in scabs to carry out the harvest. NFWA and AWOC countered by coordinating pickets around 20 or so fields a day. The picketers were often harassed – sometimes violently – by the police and grape owners. Through, in an incredible show of solidarity, many of the scabs were convinced to join the strike and grape owners soon had little leverage.

Grape owners attempted to pacify the workers with a wage increase, however, strikers also wanted a union to protect them in the future. The grape industry held fast and attempted to deny the workers a union, pushing the AWOC and NFWA to escalate their tactics. Soon after the groups campaigned for a public boycott of grapes that did not have the union label. The two groups eventually merged into what has become the United Farm Workers.

The grape strike and boycott lasted for five years but, in the end, the efforts were successful. By 1970, grape owners accepted union representation and the workers had gained better wages, benefits, and conditions. The movement represents a textbook case of grassroots activism as it shows the power grassroots can hold if they are consistent in their actions and demands.

2) Anti-Nazi Boycott | 1933

The Anti-Nazi Boycott was an international effort led by Jewish groups outside of Germany to boycott German-made goods. The movement began shortly after Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933 and was in direct response to the increasing mistreatment of the Jewish population inside the country.

The movement, however, faced serious questions around strategy as it was a delicate situation for those inside the country. German Jews even publically dismissed outside calls for boycotting Nazi Germany in an attempt to deescalate an increasingly tense and violent atmosphere. The Jewish Central Association of Germany issued a statement responding to the boycott; it stated,

“the responsible government authorities are unaware of the threatening situation,”

and

“[w]e do not believe our German-fellow citizens will let themselves be carried away into committing excesses against the Jews.”

Outside groups, however, moved forward with mass demonstrations and plans for a boycott. The American Jewish Congress led a national day of action on March 27, 1933. Rallies garnered widespread support and took place in over 70 locations throughout the U.S. Over 55,000 people demonstrated in New York alone.

The Nazis blamed the boycott on conspiracies started by “Jews of German origin.” Not long after the movement began, Joseph Goebbels began “sharp countermeasures” and led a boycott of Jewish stores and goods. The Jewish Virtual Library explains,

Goebbels announced that the following Saturday, April first, all good Aryan Germans would boycott Jewish-owned businesses. If, after the one-day boycott, the false charges against the Nazis in the overseas press stopped, there would be no further boycott of Jewish businesses. If worldwide Jewish attacks on the Nazi regime continued, Goebbels warned, “the boycott will be resumed … until German Jewry has been annihilated.”

The Nazi boycott of Jewish stores and goods was enforced aggressively by the SS. Many Jewish stores were ordered closed and some were damaged by angry crowds. The U.S. government’s response to the Nazi boycott in Germany was quite muted and downplayed reports of violence. Unsatisfied with this response, U.S. groups carried forward with the boycott as the situation simultaneously intensified inside Germany.

The Anit-Nazi boycott was soon overshadowed by the events of World War II, but it was a significant grassroots movement. This example offers important lessons for organizers acting in solidarity with other communities.

In situations such as the rise of Nazi Germany, nonlocal grassroots movements can elicit retaliation against local groups by those in power. On the other hand, some argue that these situations call for a moral imperative to draw attention to the situation. Organizers should be familiar with these concerns before acting in solidarity with other communities.

3) Singing Revolution | 1987 – 1991

The Singing Revolution was a series of protests in the Baltic States against the Soviet occupation. The demonstrations lasted from 1987 to 1991 and ultimately led to independence. Protesters showed remarkable creativity and relied heavily on signing traditional as well as modern rock songs.

Music and community festivals are deeply ingrained parts of the culture in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. During the Soviet occupation, organizers that sought independence from the U.S.S.R. leveraged that Baltic community spirit and gathered to protest under the pretext of singing. In 1988, for example, over 100,000 Estonians gathered to sing national songs for five days straight in defiance of the occupation forces.

Despite being under occupation for almost fifty years, a defining characteristic of the Singing Revolution was a prevailing sense of celebration among the protesters at these events. A leading activist at the time, Heinz Valk, wrote,

“A nation who makes its revolution by singing and smiling should be a sublime example to all.”

The solidarity between ordinary people during this period no doubt appeared extraordinary, but likely came naturally to the Baltic cultures who have long traditions of uniting around music. Those community ties manifested in other ways as well. In 1989, two million people joined arms to form a human chain linking the three capitals of the Baltic states – Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn. The chain was named the “Baltic Way” and the scene was an impressive demonstration that made global headlines.

The protests eventually became a full-fledged renunciation of Soviet rule; organizers formed alternative governments and publicly declared independence.

In August 1991, Soviet troops were sent to halt the movement and, in a profound demonstration of resolve protestors, linked arms and acted as human shields around tv and radio stations. The next day, a recent conservative coup collapsed along with the government in Moscow. The new Russian leadership withdrew the forces and recognized the independence of all three nations.

The Singing Revolution is an important example for grassroots activists as it is a clear example of how to leverage local cultures to advance social causes. The movement also shows the power of nonviolent actions to effect immense change – even against all odds.

4) International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) | 1992 – Present

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) describes itself as “a global network of non-governmental organizations, active in some 100 countries, that works for a world free of antipersonnel landmines, where landmine survivors can lead fulfilling lives.”

The idea for a campaign against landmines had sprung up independently in both Australia and the U.S. in 1991. The following year, the ICBL was formally established by six organizations working toward the goal of abolishing landmines. Jody Williams led the movement which saw tremendous success. In just three short years, ICBL grew from six organizations to a truly global movement with membership in the hundreds.

By 1997, ICBL’s efforts were well known and their demand for an international convention to abolish landmines materialized as the Mine Ban Treaty (also known as the Ottawa Treaty). The agreement was established with 121 original signatory countries and later grew to 164 total parties.

The Canadian Prime Minister at the time, Jean Chrétien, described the signing of the treaty as “without precedent or parallel in either international disarmament or international humanitarian law.” Appropriately, ICBL was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts in promoting the treaty and abolishment of landmines.

The campaign is an important example and is widely considered one of the most successful cases of grassroots activism. ICBL’s success was evident in several respects such as 1) the speed at which the movement garnered support, 2) the scale of change the campaign was able to achieve; 3) the skilled coordination among grassroots activists and government officials.

5) The Calais Movement | 2015

The 2015 Calais Movement was a grassroots effort to aid refugees near Calais, France. The movement was born out of a collective sense that European government bodies were not taking adequate steps to provide for an influx of refugees.

The movement was started by just a few individuals who were attempting to fundraise for a modest goal of $450. The appeal was met with an overwhelming response and within just five days the organizers had raised $67,000. Soon after, people began donating equipment and even trucks.

In the following days and weeks, volunteers arrived with 120 vehicles at the refugee camps to help set up proper shelter. Accounts of the event note that,

[d]entists, doctors, nurses, first aiders, solicitors, teachers, builders, carpenters, plumbers, chefs, psychotherapists, artists, musicians, and many others began offering their professional expertise.

Teenagers, students, single parents, entire families, people on work breaks, and pensioners, too, headed over to Calais to offer their general help – sorting donations in the warehouses, helping with the waste problems on-site, preparing and serving food in the kitchens set up by volunteers, helping the builders and carpenters create and erect winter-proof shelters.

The movement became a network of over 45,000 people across Europe willing to aid the incoming refugees. Volunteers contributed to significant efforts like aiding three established kitchens and over 50 community kitchens that served a combined total of over 8,700 meals a day.

Efforts disbanded at the end of 2015 as new housing developments were established for the refugees and the conditions improved significantly. The Calais movement is an example of a citizen action strategy as the grassroots response was aimed at filling a gap left by regional governments.

The efforts show that activism can take different shapes and grassroots action can be service-oriented. The scale and speed of the response helped shed light on the problem and the gaps left by regional governments. Not only did the movement help provide direct aid to the refugees, it also pressured a government response.

6) The Early Peace Movement | 10th Century – 18th Century

The peace movement is a loose term that can be applied in several different ways. The term can refer to a specific movement among a succession of campaigns starting from the 10th century leading all the way to the present day. Or, the term can be applied broadly to mean the collective peace movements throughout the ages.

The term is most often associated with modern anti-war rallies such as those during the Vietnam War. However, modern-day peace movements are legacies of grassroots efforts that began at least as early as 975 A.D. with the Peace and Truce of God movements.

The Peace of God was a proclamation by the Church (but originating from local priests) meant to protect clergy, women, pilgrims, merchants, other non-combatants and church property during a time of increased violence. Later the church proclaimed the Truce of God which sought to limit the days of the week and times of the year in which it was acceptable to wage war.

The Peace and Truce of God were widely promoted by some leaders in the church and it is considered to be one of the first documented instances of a grassroots peace movement. While it ultimately fell out of favor, the effort put into motion a social movement that has survived in various manifestations for over one thousand years. Daniel Francis Callahan notes for the Encyclopedia Britannica,

[T}he Peace of God contributed to the reestablishment of order in society in the 11th century, helped to spread recognition of the need to aid the poor and defenseless, and set the foundations for modern European peace movements.

The peace movement later resurfaced in religious life throughout Europe and North America – primarily among the historic peace churches such as the Quakers, Mennonites, and the Church of the Brethren. And, one could argue that the peace movement was rekindled in at least as early as 1660 when the Quakers denounced all forms of violence. All three churches took strict stances against serving in the military and played instrumental roles in the peace movements that followed.

By the 18th century, the peace movement had gained both secular and other religious proponents. Famous philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Jeremy Benthem wrote in defense of permanent peace and proposed world associations dedicated to the idea. Simultaneously, the evangelical religious revival in the U.S. supported a movement toward a more peaceful society.

The peace movement later grew into important efforts of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries to limit violence and end war. In fact, the modern campaigns on this list such as the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (above) and the International Campaign for the Abolishment of Nuclear Weapons (below) are rooted in these early peace movements.

The 10th-century roots of the movement, however, are seldom understood or discussed among organizers today. These grassroots origins set into motion social forces that are still taking shape over a thousand years later. The peace movement is a classic example of cause and effect in which movements started today can bring about immense changes in future generations.

7) International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) | 2007 – Present

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) is a coalition of several hundred civil society organizations representing millions of people in over 100 countries. As the name suggests, the coalition seeks the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons.

ICAN began in Australia and drew inspiration from the International Campaign to Ban Landmines mentioned above. Despite the monumental task of abolishing nuclear weapons, the coalition saw tangible results and impressive success in just ten years after being established.

ICAN focused its efforts on helping to draft and promote a treaty at the United Nations. The treaty was designed as a mutual agreement among nations to eliminate all stockpiles and future production of nuclear weapons. The proposal became reality and in 2017 the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) passed the United Nations General Assembly with 122 nations voting in favor of the treaty.

The campaign managed to leverage local grassroots support into international action and, in the same year the TPNW passed the General Assembly, ICAN was awarded the Nobel Prize. While the TPNW has not yet eliminated nuclear weapons, it is a big step in that direction and movement may yet see greater success.

ICAN is an important example for grassroots activists as it 1) demonstrates that models of international activism such as those used by ICAN and ICBL can be duplicated, and 2) that well-designed, focused, and inclusive coalitions can have a lot of success in a relatively short amount of time. However, these results are not necessarily the norm and a historical perspective would suggest that success depends on timing. As Victor Hugo noted, “nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

8) The Candlelight Revolution | 2016 – 2017

The Candlelight Revolution was a series of protests in South Korea that lasted from October 2016 until March 2017. The protests called for the resignation of the South Korean president at the time, Park Geun-hye. In all, more than 16 million protestors filled the streets in peaceful demonstrations.

The demonstrations began when it was uncovered that Park Geun-hye had been receiving secret counsel from Choi Soon-sil, a leader of a religious cult who held no official position in the government.

Despite her lack of security clearance, Choi had been privy to classified information and was found to be the primary architect of many government policies. Later revelations showed that Park and Choi had conspired to extort hundreds of millions of dollars from large family-owned businesses.

The first rallies began in October of 2016 with relatively modest crowds of around 20,000 demonstrators. By early-November, the numbers began growing quickly. Police reported that on November 5th around 43,000 protestors filled the streets, while organizers reported over 100,000 protestors on the same day.

By December 3rd, 2.3 million South Koreans flooded the streets calling for the ouster of Park. That single day marked the largest demonstration in the country’s history. Throughout the fall, protestors had been holding candlelight vigils into the night and on December 3, 2016, the image of millions of South Koreans holding candlelight demonstrations made its way around the world.

Counter-protests began in December as well when pro-Park demonstrators began holding rallies in nearby locations. The counter-protesters were largely composed of older voters who criticized the attempts to impeach Park as being “misguided.” Pro-park demonstrators argued that the media had been focusing on the opinions of young liberal voters and exaggerating certain aspects of the scandal.

Nonetheless, candlelight protesters continued to hold demonstrations and braved the snow and cold throughout the winter. As the situation unfolded, organizers maintained their call for Park’s resignation while, at the same time, remaining nimble in their demands in order to respond to the twists and turns of the impeachment proceedings.

Both sides of the controversy had gained considerable support on the streets of South Korea throughout the winter and into the spring of 2017. By March, 16,000 police officers were dispatched to maintain a barrier using over 100 buses to separate the opposing camps. Ultimately, Park was impeached in March 2017 and the candlelight protests proved to be a tremendous example of the grassroots reforming a political office outside of the election process.

The movement is a critical example for activists as it shows that sweeping change can happen in a relatively short amount of time – if enough people participate consistently. Organizers of the movement did not receive as much attention in the press as they likely deserve, however, given that part of the movement’s success was, at least in part, due to its ability to respond to key procedural hurdles in the impeachment process.

9) The Temperance Movement (U.S.) | Early 1800s – 1933

The Temperance Movement in the U.S. was an effort to make the production and consumption of alcohol illegal. Grassroots efforts lasted over a century and eventually succeeded in 1919 with the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The measure was later repealed in 1933, however.

It’s worth noting that temperance movements have occurred in many places throughout history. Even today, long after the repeal of Prohibition in the U.S., these movements still exist and their impacts can be found throughout the country; hundreds of municipalities still prohibit the sale and consumption of alcohol.

The Temperance Movement in the U.S. is an important example of grassroots activism as it lasted over a hundred years. The efforts began in the early 19th century among churches who saw it as part of larger moral reform efforts. The idea, though, proved to have traction in its own right and by 1833 there were 6,000 local organizations dedicated to temperance alone.

In various stages of the movement, activists were split between advocating for total probation (teetotalism) or simply moderation. Conflicts arose between the advocates because those in favor of moderation considered drinking to be culturally important. Nonetheless, a wider movement around alcohol consumption gradually began shifting public opinion.

While in today’s context the measures may sound extreme, alcohol consumption was a much more widespread and serious issue at the time than it is today. In 1833, the average American consumed 7.1 gallons of pure alcohol a year; today, Americans consume on average around 2.3 gallons a year.

By the later half of the 19th century, local movements began to transition into national organized efforts. For example, in 1869 the Prohibition Party was founded as a spin-off of efforts by the International Order of Good Templars (the largest organization devoted to the issue). The Party sought to elect leaders willing to take action and pressure other parties to pass reforms. Political candidates in both parties had largely avoided the issue because both parties were sharply divided on the issue.

The movement was also set against the backdrop of changing social norms. Women played an outsized role in the movement and temperance had been regarded as a major social issue of the time alongside slavery and women’s suffrage. In 1873, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was established and it later came to play an influential role in the temperance movement as well as other progressive movements at the time. WCTU is often regarded as one of the first international women’s organizations.

Toward the end of the 19th century, local laws began closing bars and pubs across the U.S. and Europe. Eventually, political support for the idea forced the U.S. Congress to act. Pressure tactics had been perfected by the Anti-Saloon League which, led by Wayne Wheeler, would cover the desks of legislators with telegrams rather than ask for a vote directly. The tactic was even nicknamed “Wheelerism” and remains grassroots activism 101 even today.

Wheeler’s efforts were widely considered to be a primary force for passing the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, which prohibited the sale and consumption of alcohol. The law, however, had some unintended consequences on society. While there is evidence to suggest that prohibition had positive impacts on things like adult learning, the law also had negative consequences such as the illegal production and sale of alcohol, difficulties in enforcement, economic fallout, and much of the mobster violence of the 1920s.

For these reasons, the movement eventually fell out of favor and, in 1933, the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed. The movement is a particularly significant (though not necessarily popular) example for grassroots activists for several reasons.

First, the movement shows the difficulty in addressing public health issues through legal means. Second, the history of the movement is a clear example of how political trends shape grassroots activism and how today’s progressive movement may become tomorrow’s conservative cause.

Third, the movement’s strategy could be described as a social transformation model and it may represent one of few cases in which the model was applied successfully only to have it overturned at a later time. Temperance, then, challenges the notion that social transformation models inherently create longer-lasting and more stable reforms.

Finally, Wheeler’s tactic at barraging lawmakers with messages from constituents is a tactic that most grassroots activists take for granted today. However, the innovation of Wheelerism was a revolution at the time and it marked a new age in grassroots activism.

Looking for some grassroots strategies? Check out these seven fundamentals.

Recent Posts

Writing a letter to the president can be an effective way for advocates to have their voices heard, influence policy decisions, and move public opinion if done with some planning and intentionality....

This is a straightforward guide for organizers who are planning protests. The below sections layout the logistics of organizing a demonstration, strategies, and tactics, and how to leverage the event...