Writing a letter to the president can be an effective way for advocates to have their voices heard, influence policy decisions, and move public opinion if done with some planning and intentionality. The vast majority of letters to the President go largely unheeded because of the sheer volume of letters received and the lack of planning and follow through on the part of the authors. This post lays out step-by-step how to send a letter to the President and how to have the biggest impact possible.

To send a letter to the president of the United States, authors may use this electronic contact form on the White House website or send a paper copy of the letter to The White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20500.*

Despite the ease of communication today, authors should use this process sparingly and carefully time their efforts to maximize impact. Advocates should also be prepared to do outreach to and coordinate with supporters, allies, the media, and other public officials before sending the letter. Over several years, I have led many civil society efforts in writing to the president and, while many factors are outside of the control of organizers, there is more or less a formula for maximizing impact.

Advocates, of course, never cease to be creative and this “formula” is a series of best practices I have accumulated in my work; it’s not meant to be a rigid process nor does it guarantee any type of success.

*Note that some websites still direct readers to the old White House email addresses (president@whitehouse.gov; vice_president@whitehouse.gov, comments@whitehouse.gov); however these email addresses have not been active since the Obama years when much of the administration transitioned to using contact forms. Always check the White House website for the most up-to-date contact method.

Getting Your Message in front of the President

Best Practices for Content & Timing

Sample Letter to the President

Garnering Additional Support and Signatories

Generating Media Buzz & Publicizing the Letter

Additional Actions to Reinforce the Impact of Your Letter

If you’re just getting started with advocacy, I highly, highly, highly recommend you get the book Organizing for Social Change (4th edition) put out by the Midwest Academy. You can find the book on Amazon through our affiliate link here.

Getting Your Message in front of the President

Getting a message in front of the president is understandably a difficult task and, in order to be effective, the logistics of sending a letter should be carefully thought through. Just using the White House contact form is sufficient, but there are plenty of things that advocates can do to help give their message the best chance of being heard.

To begin, a case can be made for sending the letter through both the contact form and through the regular snail mail. This gives your letter two chances of being “logged” by White House staff. Trust that the letter will be read by someone, but when the letter is received it will likely be entered into a database and categorized according to the issue by a White House staffer (potentially an intern).

What happens from the point of the letter being logged likely varies greatly by the administration, staff, and the letter’s message and quality. There is no guarantee that the message will ever reach the president, but advocates can improve their chances by sending the letter to other officials in the administration as well as their members of Congress (more on that below).

Identifying other relevant officials and sending the letter to their office provides advocates with more chances of the message being logged. For example, if an advocate were writing a letter concerning farming practices, they could also send the letter to the Department of Agriculture. Often, specific bureaus, offices, and personnel can all be identified within relevant Departments, offering more entry points for advocates to send their message. Advocates should seek to find as many relevant contacts as possible.

Truthfully, the best way to identify and contact officials in the administration is through paid-for services such as Leadership Connect or Bloomberg Government. These types of web services offer up-to-date directories of government officials, which can be invaluable – especially when trying to contact senior officials. However, these services can be pricey, and sending letters through publicly available contact information can work if these tools aren’t available.

Best Practices for Content & Timing

Letters to any public official and especially the president should always be concise. Whoever receives the letter is likely a very busy person. So, authors should boil the message down to as few words as possible to increase the chances the message will be read and understood. Additionally, the tone of the letter should always be respectful even when passions are high; using diplomatic language does not betray an advocate’s position, but offers the best chances at advancing civil discourse.

The first paragraph should provide a clear and concise introduction of the authors and the reason for writing. For example, “Dear President [Last Name], As a network of environmental, faith-based, human rights, and other civil society organizations, we write to urge you to…” If you’re writing as an individual or group of individuals, state your connection to the issue and any relevant expertise.

The following paragraph or paragraphs should state the “ask” (or what the author would like the president to do). Asks can be general such as “stop the war” or very specific such as “repeal National Security Directive X section (Y) paragraph Z…” If there are several asks, try to boil them down and list them in a bullet point format.

After the ask is clearly stated, the following paragraphs should be the best arguments for why the president should listen to the authors. This should be the best support material advocates have for their case. Authors might want to cite research, quote experts or other public officials, provide powerful anecdotes, or state their most convincing talking points. Don’t be afraid to use footnotes!

A good practice is to wrap up with a summary paragraph and finish with a congenial conclusion thanking the president for their consideration. The letter should be no more than around 3 pages. Authors can provide supporting material such as a report by attaching the documents and referencing the attachments in the body of the letter.

Authors should also consider the timing of sending the letter. Generally speaking, the beginning of a new administration (or new term with an incumbent administration) is one of the best times for a message to be heard. Presidents and their staff conduct policy reviews when they enter office and it can be a perfect time to provide input (especially because many career staffers are looking for ideas to present to their new bosses). Other good times to send a letter include when the issue is in the news, when Congress takes a relevant action, ahead of a major relevant event, after a sudden relevant incident, or when coordinated with other high-profile advocacy initiatives.

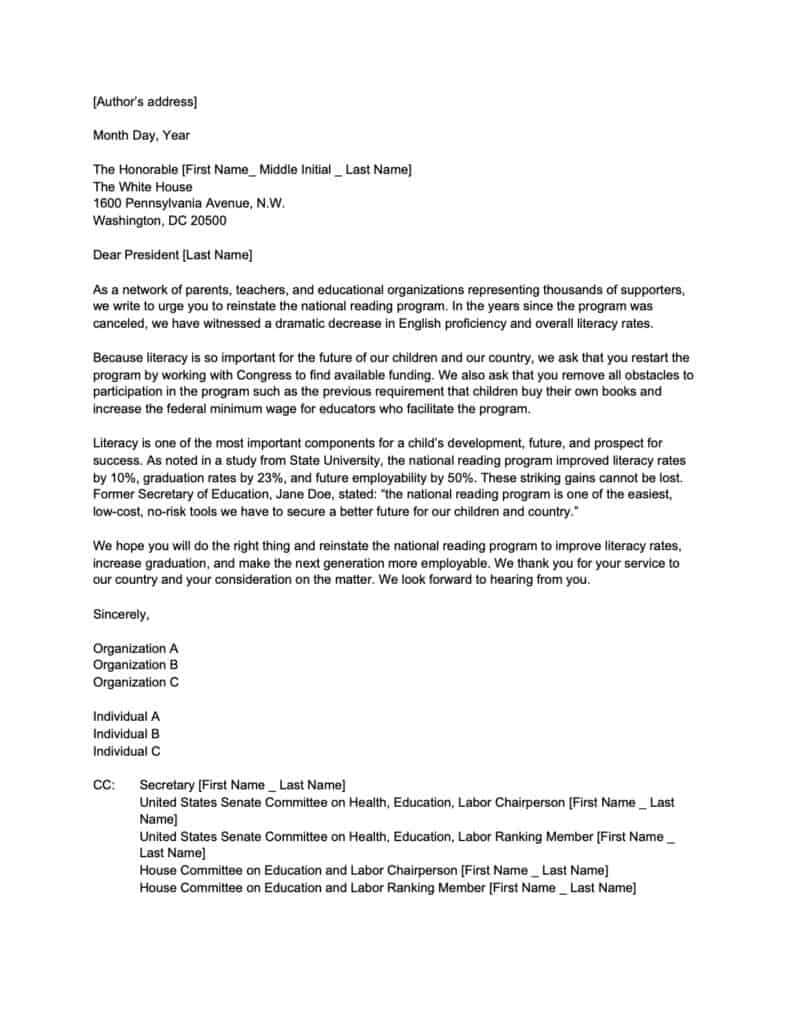

Sample Letters to the President

Below is a free downloadable example of a letter to the president. The example uses a fictional national reading program for illustrative purposes.

Garnering Support and Getting Additional Signatories

Letters to the president are always more powerful when sent by a group of people and/or organizations. To get allies on board it’s best to work with a small group first to help draft the letter. Writing the letter by consensus helps ensure more interests are represented and should give the letter a sharper message.

Once the draft is agreed upon, the small group of authors should decide on how a few key factors on how to handle endorsements. Questions to consider include:

- Will organizers accept signatures from individuals, organizations, or both?

- If organizers collect both, it’s important to have a good organization to individual ratio. Having more individuals than organizations is usually ideal (a 2:1 ratio is a good rule of thumb). Though, high-profile figures such as former government officials or celebrities may be an exception.

- Will organizers accept signatures from affiliate offices or only take endorsements from national/headquarter offices?

- Some organizations operate based on satellite offices; these offices sometimes have the authority to sign on their office but not the organization as a whole. For example, a group may sign as ‘Advocacy Action – Pittsburgh Office.’ Organizers should agree if they will take chapter endorsements or only national/headquarter endorsements.

- Will organizers accept international endorsements?

- Individuals and organizations that are not from the U.S. may want to join the letter; however, the president is not accountable to these groups and so their signature carries less weight. These organizations can still be added to the letter to make a point so long as they are credible, verified, and clearly indicated to be from outside the U.S.

Once organizers have an understanding of how to handle endorsements, advocates can circulate the letter to listservs and contacts to solicit signatures. It’s most effective to indicate the original group of authors when asking for signatures to show initial support for the effort. Set and indicate a deadline to sign on and try to give it as much time as possible.

Pro-tip: Google forms is a great way to collect signatures and build lists for future efforts. When asking for signatures, it’s good practice to collect the following information:

- Name of Individual/Organization

- Name of contact

- Email of contact

- Approximately how many supporters (defined by membership, email lists, etc.) organizational sign-ons have

- Location/Origin: U.S. based or international

Generating Media Buzz & Publicizing the Letter

A letter to the president is a good opportunity for advocates to engage the press with their message (don’t overlook local media either). Before sending the letter, the authors can draft a press release to issue on the day they send the letter. Typically, a press release contains a few quotes provided by the primary authors so journalists have something to grab for a story. If organizers have enough lead time and significant support for their letter, they can try to work with a reporter the day before the letter is sent so that the story appears first thing in the morning.

Additional Actions to Reinforce the Impact of Your Letter

Complimenting the letter with other actions or a series of actions can increase the impact of a letter exponentially. However, organizing becomes more complicated and usually needs more lead time. If organizers have the capacity, they may want to consider complementing their letter to the president with the actions such as:

- Writing and placing op-eds before or immediately after the letter is sent.

- Demonstrations such as protests, vigils, etc.

- Asking members of Congress to send a similar letter or to speak with the administration about the issue.

Recent Posts

This is a straightforward guide for organizers who are planning protests. The below sections layout the logistics of organizing a demonstration, strategies, and tactics, and how to leverage the event...

This is a user-friendly guide to effective protesting. Topics include individual involvement, what to know before joining a protest, what to wear, on-the-ground tactics, encounters with law...