Every day there are countless examples of successful advocacy campaigns. The beauty of advocating is that success can come at any scale ranging from a single individual to a group of dedicated professionals to large social movements.

The business of advocacy, though, can often blend with public education, an equally important activity, but one with more intangible outcomes. To help show some of the structural changes that advocates can acheive, below are 7 examples of advocacy that resulted in concrete policy change.

The list includes examples from all types of advocates ranging from organized movements to teenagers with a vision. What’s important to keep in mind is that we are looking at specific victories from these advocates, but most of the activists and organizations mentioned below carried on campaigns well before and after these moments. At times, some were even conducting multiple campaigns simultaneously. This goes to show that advocacy is a long game; one that often develops through a series of changes to policy and public opinion.

- The Section 504 Sit-in & the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

- The National Child Labor Committee & Child Labor Laws

- Ralph Nader & Unsafe at Any Speed

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature & Wildlife Trafficking Laws

- The National Organization for Women, Bernice Sandler, & Gender Equality in Education

- Wijsen Sisters & Bali’s Plastic Bag Ban

- The Nuclear Freeze Campaign & US-Soviet Arms Control

1. The Section 504 Sit-in & the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

The disability rights movement is not etched into our collective memory like the struggle for racial and gender equality; however, disabled rights advocates were a critical wing of the larger civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Nonetheless, it wasn’t until the 1990s that discrimination against disabled persons was prohibited by law in the same way as racial or gender discrimination had been prohibited decades earlier.

A key juncture for the disability rights movement came in 1977 when advocates became exasperated with officials who were delaying the implementation of a four-year-old law meant to protect the rights of disabled persons.

The law, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, prohibited discrimination based on disability for programs that received federal funding. While the Nixon and Ford administrations developed regulations for Section 504, they never put them into effect. By the time Jimmy Carter took office, disability rights activists were tired of waiting and determined to force the new administration to put into place equal protections.

Activists rallied to pressure the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Joseph Califano, to sign the measures and implement them by April 5 (1977). If the deadline was not met, the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD) vowed to take action.

The deadline came with no movement from Califano and, as promised, the ACCD took action. The organization and disabled rights activists like Judith Heumann and Kitty Cone organized a sit-in at a federal building in San Francisco.

At first, the protestors were not taken seriously. HEW employees even handed out punch and cookies to the activists. Heuman recalled that they treated them “as if we were on some kind of field trip.” It didn’t take long, however, for the activists to show their determination.

In all, around 150 activists maintained the sit-in for 25 days – a lengthy action for the spriest of activists. Many genuinely risked their lives to participate as they lacked access to medications, equipment like ventilators and catheters, and assistance from health care professionals.

Despite the hardships, the sit-in represented an empowering moment for disability rights advocates. Cone later described the event as “the public birth of the disability rights movement… For the first time, disability really was looked at as an issue of civil rights rather than an issue of charity and rehabilitation at best, pity at worst.”

On April 28, 1977, Secretary Califano signed Section 504 and began the implementation of the regulations. The sit-in is a classic example of how grassroots activism is often needed to complement advocacy and lobbying. When policy gets stalled, collective action is usually required to push an issue forward.

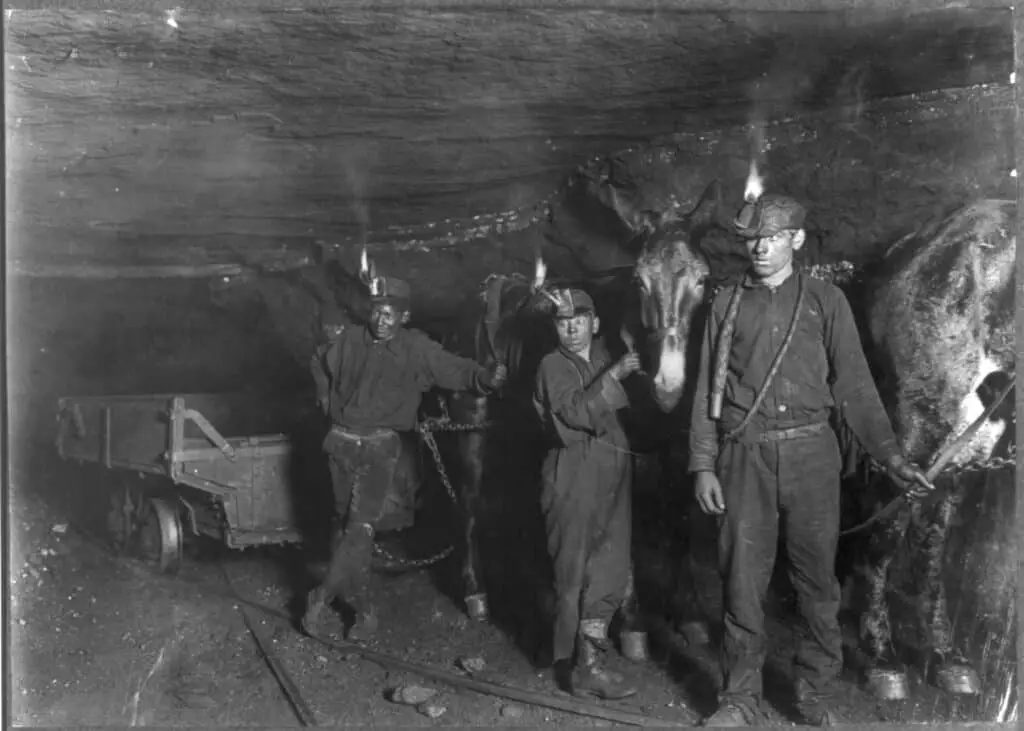

2. National Child Labor Committee & Child Labor Laws

Child labor had been a consistent practice in the U.S. from the country’s beginnings, and the demand for cheap labor only accelerated with the Industrial Revolution. By 1900, 18% of the U.S.’s labor force was made up of children under the age of 16.

Opposition to child labor, however, had been steadily increasing in the late 1800s among reformers and, at the turn of the century, these advocates formed the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC).

The NCLC became one of the most innovative social reform organizations of its era, using an array of effective tactics to sway public policymakers and the public. According to History.com,

The National Child Labor Committee, organized in 1904, and state child labor committees led the charge. These organizations employed flexible methods in the face of slow progress. They pioneered tactics like investigations by experts; the use of photography to spark outrage at the poor conditions of children at work and persuasive lobbying efforts. They used written pamphlets, leaflets, and mass mailings to reach the public.

These tactics gained traction over time and the NCLC began to convince both lawmakers and the public that child labor needed to be regulated. A series of state laws began to pass until the Supreme Court struck down key cases in 1916 and 1918.

Later, the group and other reformers sought a Constitutional amendment to regulate child labor. While they succeeded in getting an amendment was passed by Congress, it was never ratified by the requisite number of states. Thus, it has never become part of the Constitution.

Ultimately, it wasn’t until the Great Depression that reformers were able to make a significant change. As policymakers sought to reduce adult unemployment, advocates used the moment to push for further child labor regulation.

NCLC and its network of state committees succeeded; many protections were then put into place with Roosevelt’s New Deal along with the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The tactics developed by the NCLC (particurly photo-investigative tactics) are key tools for many human rights advocates today. While child labor has not entirely disappeared from the U.S., the sweeping changes brought on by the NCLC provides a textbook example of effective advocacy.

3. Ralph Nader & “Unsafe at Any Speed”

Despite having some vocal critics, Ralph Nader achieved one of the quickest and most successful examples of advocacy in the modern era. Not only was Nader able to achieve sweeping change in the automotive industry, but he also did so with remarkable speed and primarily as an individual.

Nader initiated a tectonic shift in the way the public, the government, and the automotive industry viewed motor vehicle safety with his book Unsafe at Any Speed. He reportedly had the idea of publishing on the topic after he conducted research while attending Harvard Law School. Nader had became alarmed over the auto industry’s reluctance to incorporate safety precautions in their engineering.

Publishers, however, were quite skeptical of taking a chance with Nader’s proposal for a book on car safety – one even remarked it was material meant “primarily for insurance agents.”

Finally, one publisher took a chance, and, almost immediately, the book sent shockwaves through the public and the US government. Nader was quickly asked to testify at a hearing in front of the U.S. Senate, which ultimately led to the passage of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act – just ten months of the book’s publication.

The Act required regulators to determine safety standards for the auto industry, which ultimately led to many of the safety regulations we are accustomed to today including head rests, shatter-resistant windsheilds, and seatbelts.

Later, the book even inspired the creation of a new federal agency – the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Nader’s success, though, was not just due to his writing, he also understood how to advocate skillfully. Joan Clayborn, who lead the NHTSA in the 70s, told the New York Times,

He played a critical role in a very subtle way by using contacts with the media, communicating with them almost every day, giving them new ideas and new stories, talking to whistle-blowers.

Nader’s success demonstrates that an individual can make a massive difference when they advocate patiently. His story also shows that issues that might sound mundane to people at first can quickly become the talk of the town if the message is framed well.

4. International Union for Conservation of Nature & Wildlife Trafficking Laws

The widespread stigma around wildlife trafficking today has its roots in some brilliantly straightforward advocacy by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The impact of the IUCN on wildlife trafficking laws around the world is a testament to what advocates can do when they build up credibility and expertise on issue areas.

IUCN was founded in 1948 and the organization focused heavily on documenting the impacts of humans on the environment for the first twelve years. Among many other issues, the organization looked at the impact of the wildlife trade and found alarming results.

Later the organization branched into other activities and during a conference in 1963, members adopted a resolution outlining the need to protect species and ecosystems. The resolution, endorsed by scientists and researchers, allowed advocates to make their case to governments around the world.

That resolution, adopted by a private organization, ultimately inspired a multinational agreement to limit the trade of endangered species. The agreement, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora or CITES), was signed by 80 countries in Washington, DC in 1973.

CITES remains a key regulatory component in combating the trafficking of endangered species worldwide. IUCN’s use of “in-house” expertise to demonstrate the need for global cooperation is noteworthy for students of advocacy.

Keep in mind, however, that since the adoption of CITES the organization has had to work tirelessly to ensure states maintain compliance with the treaty. Nonetheless, CITES marked a turning point in the issue and since it’s adoption, environmentalists have had global regulations on their side.

5. National Organization for Women, Bernice Sandler, & Gender Equality in Education

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which instituted several regulations banning discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, some gaps in the new regulations became apparent. One major example was that the act did not end discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded education programs.

The National Organization for Women (NOW) spearheaded efforts to remedy these missing elements to the civil rights laws. In doing so, the organization ultimately laid the foundation for a critical measure in ending gender discrimination – Title IX.

Prior to Title IX’s passage, NOW found a critical way of moving gender equality forward. The group lobbied President Lyndon Johnson, White House aides, and Members of Congress to include women in an Executive Order (11375) that prohibited discrimination in federal contracting.

The group’s lobbying paid off and Johnson including prohibitions on the discrimination of women. The measure opened the door for women who were being discriminated against to seek recourse.

A major success of the new law came from a notable activist, Bernice Sandler, who used the Executive Order to file 269 complaints against 250 colleges and universities for various discriminatory practices. Sandler worked with NOW to utilize the complaint procedures elevating her profile in Washington. Later she proposed the idea of Title IX along with Representative Edith Green in a committee hearing.

Title IX, which prohibits discrimination in education based on sex, later become law in 1972, giving women equal access to educational opportunities. NOW’s early advocacy efforts show the power of what many call today “intersectionality” as they further cemented gender in the larger civil rights discussion.

The cooperation between NOW and Sandler demonstrated two things:

- how incremental policy movements can serve as springboards for larger reforms, and

- how groups and activists often collobarate to create change.

6. Wijsen Sisters & Bali’s Plastic Bag Ban

Melati and Isabel Wijsen are testaments to the impact that youth (or anyone) can make in the world with a simple determination to act. The sisters grew up in Bali, Indonesia and at the age of 10 and 12 became concerned about the amount of plastic accumulating on the island.

Melati told CNN in 2017,

There’s no escaping it here. The plastic problem is so in your face, and we thought: ‘Well, who’s going to do something about it?

One day at school the sisters were struck by inspiration when learning about positive world leaders like Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr, and Princess Diana. Later, after learning about a polyethylene ban in Rwanda, they had an idea of how to tackle the plastic problem at home. In the same 2017 interview with CNN, Melati declared

We didn’t want to wait until we were older to stand up for what we believe in.

With that determination, the sisters started an NGO called Bye Bye Plastic which sought to rid Bali (and the world) of plastic bag use. It wasn’t long before the two became an internationally known advocacy duo calling attention to the shocking reality of plastic bag consumption. The two gave a crowd-favorite TED Talk in New York (embedded above) and delivered a speech at the United Nations (embedded below).

The sisters, though, were not just good at public education; they also carried out a strategic advocacy campaign. In addition to direct lobbying, they started a petition and were able to obtain permission to collect signatures from behind customs and immigration at Bali’s airport. They collected over 100,000 signatures supporting a ban on plastic bags.

The governor of Bali, Mangku Pastika, was not moved by the girl’s advocacy or petition, however. Feeling stuck, Melati and Isabel thought to use what they had learned about Mahatma Gandhi’s activism while on a trip to India – they decided to go on a hunger strike.

Because they were children, a dietician oversaw the action and it was only carried out from sunup to sundown. Nevertheless, the hunger strike worked. After just one day, the governor summoned the girls and signed a memorandum of understanding to help stop plastic bag use in Bali.

While young, the Wijsen sisters have earned a spot as an instantly classic example of advocacy. The two are perfect examples of how to build public support, execute an advocacy campaign, and how to leverage notoriety.

7. The Nuclear Freeze Campaign & US-Soviet Arms Control

The Nuclear Freeze campaign was one of the most organized and effective social movements in history. The movement demonstrates the power of collaborative advocacy and grassroots action even against the most monumental of odds.

The movement began in 1979 as a proposal from an American researcher and advocate, Randall Forsberg. Forsberg suggested that peace organizations unite around a call for the U.S. and Soviet Union to halt the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons. It quickly gained public support and ultimately helped usher in an era of nuclear arms control.

Initially, Forsberg sought the endorsement of a few key organizations to support her “Call to Halt the Nuclear Arms Race.” Along with the think tank she founded, the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies, Forsberg secured the support of faith-based groups like the American Friends Service Committee, the Clergy and Laity Concerned, and the Fellowship of Reconciliation. From there, the movement snowballed, gaining support from the general public, leaders, intellectuals, activists, and officials.

At the time, the U.S. and Soviet had over 50,000 nuclear weapons – with plans to develop 20,000 more. These startling realities coupled with other public education devices like movies and books led to a profound public reckoning. This, in turn, led to a flurry of grassroots organizing.

The campaign centered around the mantra “think global, act locally” and as a result, a plethora of grassroots advocacy at the local level ensued. By 1983, the “Call” had been endorsed by 23 state legislatures, 71 county councils, and more than 370 city councils.

While the movement struggled to push forward a resolution in Congress and to shift the Reagan administration’s position, the overwhelming public support for the campaign forever altered the political discussion around nuclear weapons.

In 1985, six years after the Freeze Campaign began, Mikhail Gorbachev, who was, by his admission, deeply influenced by the Freeze Campaign, came to office in the Soviet Union. Not long after, a series of negotiations with the Reagan and Bush administrations led to the creation of several key nuclear arms control agreements including the INF Treaty, the START I Treaty, and START II Treaty.

While the Freeze Campaign unfolded on a much larger scale than the average advocacy campaign, it’s a stark reminder of the power of the grassroots to dramatically alter the trajectory of a nation – and the planet.

Looking for more on advocacy?

- If you’re looking for examples of social media advocacy, check out our post on the impact of social media on politics.

- If you’re looking to understand day-to-day advocacy, check out our post 31 strategies and methods that advocates ACTUALLY use.

- If you’re trying to understand more about how advocacy basics, check out this post.