While the impact of social media on politics seems to be changing all the time, some consistent trends are emerging.

Research shows that social media can have a minor but still significant influence on voter behavior. Social media has improved information flows, outreach, mobilization, and fundraising; however, it has also increased surveillance, political polarization, the spread of misinformation, and harassment.

Each aspect of social media’s influence on politics is the subject of ongoing research and debate in political science.

At the same time, policymakers are increasingly scrutinizing social media platforms, particularly in the domains of data privacy, innovation, and the spread of misinformation. Social media has big implications for advocates of social causes too as the platforms provide an innovative way to spread messages.

An often overlooked aspect of social media’s impact on politics, however, is that communities across the world have formed different relationships with these platforms. The new media is a double-edged sword for politics, giving space to some while making others targets.

It’s important that each of the above perspectives is included in our understanding of the role of social media in politics. This post, then, will give an overview of how these platforms impact politics by exploring political science research, cyber policy, grassroots advocacy campaigns, opinion polls, and public surveys. The sections below will also focus on key real-world examples to help illustrate these concepts in action.

Below the post is divided into the following sections:

- Social Media Meets Politics: A Brief History

- Social Media and Civic Engagement: Three Theories of Impact

- “Clicktivism” – Mobilization theories

- Political Action and Social Media: The Arab Spring

- Political Tools on Social Media: Change.org

- Political Campaigns on Social Media: “El Bronco”

- “Slacktivism” – Cyber Skepticism

- Political Messages and Viral Trends on Social Media: Kony 2012

- Local Politics as a Global Social Media Discussion: #BringBackOurGirls

- The Thin Line Between “Activism” and “Slacktivism”

- “Big Brother Bubble” – Reinforcement Theories

- Internet Freedoms in the Global Context

- Surveillance Capabilities: XKeyscore

- Political Marketing and Privacy: The Case of Cambridge Analytica

- Politics and Social Media Access: Sudan’s 2019 Protests

- Political Censorship and “Fake News” on Social Media

- Political Interactions and Harassment on Social Media

- Politicians, Free Speech, and Harassment on Social Media

- Politics, Identity, and Social Media

- “Clicktivism” – Mobilization theories

Social Media Meets Politics: A Brief History

While the web began to have a small impact on politics in the United States as early as 1996, it wasn’t until later that social networking sites became viable web-based tools for campaigns.

At first, the impact of social media was almost exclusively on youth. According to the Pew Research Center, during the 2008 election season over one-quarter of voters under the age of 30 found information about political campaigns on social media. Virtually no voters over the age of 30, by contrast, retrieved political information on social media during that same period.

Just ten years later in 2018, over half of all U.S. adults reported that they had been ‘civically’ active on social media in the past year. In the span of a decade, social media went from largely being a youth phenomenon to becoming an established information-sharing platform in the U.S. and other parts of the world.

While social media remains one of many online tools, the platforms do seem to have a number of unique impacts on voters and campaigns. From the perspective of campaigns, social media was the missing link between internet activity and in-person political action.

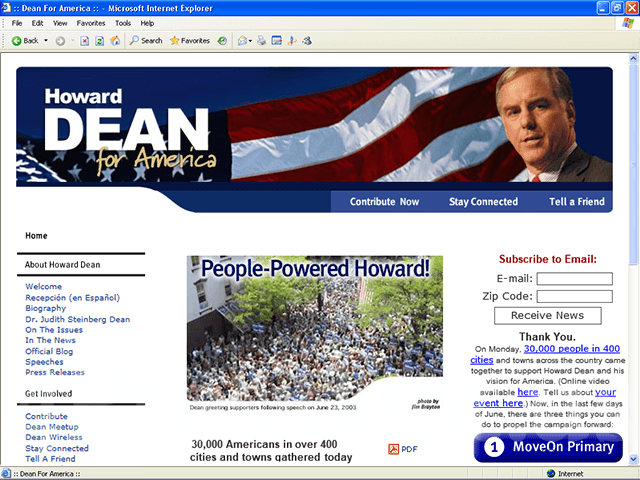

Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign is recognized as being the first campaign to capitalize on the power of the web and social media for political mobilization.

In the realm of social media, Dean’s campaign was able to utilize Meetup.com (a website that allows users to find interest-specific events) as a way for supporters to organize and hold local rallies.

Without centralized coordination though, the local events often failed to produce sustained activity from supporters after the events ended. It wasn’t until the 2008 Obama campaign that social media became a way of coordinating locally-organized events with a national campaign strategy.

Social Media Campaigns: Social Movement or Hyper Political Marketing?

The 2008 Obama campaign spread quickly on social media which may have helped the campaign to capture the youth vote. A Facebook group called “Students for Barack Obama,” for instance, spread to eight campuses and began to operate much as a campaign would with coordinators for various roles including finance and blogging.

Students who had initially joined an online group became volunteer coordinators in ongoing roles. This type of consistent engagement from online volunteers was what the Dean campaign couldn’t realize in 2004.

The Obama 2008 campaign, on the other hand, mobilized support so effectively that it is often cited as part of the reason he won 66% of the youth vote that year; though, social media was likely one factor among many.

The campaign generated some attention among political scientists. Researchers at Chapman University, for example, argued that the 2008 Obama campaign was able to harness social media in a way that resembled a social movement instead of an organized political campaign.

The argument is partly rooted in how information flows over social media. Social media allows information to flow from the producer to the consumer and from the consumer back to the producer – quickly and publically. As a result, messages became more “peer-to-peer” as campaigns hone their ads to constituent behavior.

This type of information flow created what some have called the “prosumer” – an actor that both uses and helps shape information or products produced by others (producer + consumer = prosumer).

While the “prosumer” does speed up feedback loops for campaign messages, it does not necessarily change the centralized and bottom-down nature of political messaging.

Social movements, in contrast, create messaging around issues and concerns of impacted communities as opposed to a single politicians platform. Hence, social movements flow bottom-up – allowing their message to be shaped by people’s circumstances as opposed to top-down political agendas.

In hindsight, then, the use of social media by the Obama campaign could be understood not so much as a social movement but, simply, how political campaigns function over social media.

Obama’s 2008 campaign, though, may have been the beginning of something more troublesome – hyper-political marketing. Hyper-political marketing is a phenomenon resulting from the plethora of voter data available on the web and social media. The term (as used on this website) describes the use of vast amounts of user data to target and disseminate messages for political purposes.

The Chapman University study linked above discussed the Obama campaign’s use of cookies to target ads. While cookies are commonplace today (this website uses cookies), they allow targeted political ad campaigns to become so specific and repetitive that they create an ‘information bubble’ around users.

This ‘information bubble’ contributes to political polarization and a break down in public dialogue (see the section below on ‘Big Brother Bubble’ for more) as users become less exposed and less receptive to opposing points of view.

Tellingly, the amount of money spent on online and social media political ads is increasing at a breakneck speed. During the 2008 election season, Obama spent just $16 million, and John McCain just $3.6 million on online advertising. Expenditures for the same type of ads skyrocketed 355% (adjusted for inflation) in the ten years since the 2008 election. In the 2016 presidential race, the Trump and Clinton campaigns spent a combined total of $81 million on Facebook ads alone.

Political campaigns, then, continue to keep pace with social media developments and have become increasingly sophisticated at using the platforms to control information flows. Evident from the beginnings of social media and politics is that social media has a multifaceted impact on voter behavior – an impact that has only grown more complex as social media use changes.

Social Media and Civic Engagement: Three Theories of Impact

Theories of the internet’s impact on politics are also useful frameworks for looking at the more specific question of social media’s impact on politics.

In the past, these theories have been divided into at least three categories:

- “Clicktivism” (or mobilization theories) – suggest that the internet (or social media in this case) will make civic participation easier and faster.

- “Slacktivism” (or cyber skepticism theories) – suggest that the internet (or social media in this case) has no impact on civic engagement and may even decrease participation by replacing meaningful political action with less meaningful online activity.

- “Big Brother Bubble” (or reinforcement theories) – suggest that the internet (or social media in this case) will strengthen existing power structures and further fragment political identities.

The debate between these theories is ongoing, and each has found compelling evidence for their claims. All three categories, though, accurately depict different aspects of the same phenomenon and we may need to accept all three as simultaneously valid.

“Clicktivism” – Mobilization theories

Growing evidence suggests that the internet has produced innovative means of promoting civic engagement.

A 2014 survey of Malaysians, for instance, demonstrated that engaging over social media increased citizen’s trust in institutions. Authors noted that when social media users were confronted with civic-related posts they felt more urgency to get involved and take action.

Researchers concluded that institutions needed to engage more with the public on social media or public participation would continue to decline. While there have been many failed attempts at promoting civic engagement online, there may be just as many success stories. Below are just a few examples of social media playing a role in large civic actions.

Political Action and Social Media: The Arab Spring

Social media proved useful in mobilizing supporters for the 2008 U.S. presidential political campaigns, but whether the platforms could be useful for mobilizing bottom-up social change was another question entirely.

About two years after the “Facebook Election” (as it had become known) a wave of demonstrations took place in the Middle East which later was collectively dubbed the “Arab Spring.” Beginning in Tunisia, street protests erupted in 20 countries over the course of a little over a year and a half. Commentators were quick to point out that social media seemed to be playing a major role in the demonstrations.

The new media began filling gaps for organizers in countries where state-owned media restricted information flows. While a democracy movement had been brewing for some time in the Middle East, many argued that social media allowed for the rapid spread of organized civil action.

Some optimistic scholars even went so far as to suggest that social media was the defining aspect of the revolutions. Research out of the University of Washington, for example, stated,

Digital media became the tool that allowed social movements to reach once-unachievable goals, even as authoritarian forces moved with a dismaying speed of their own to devise both high- and low-tech countermeasures.

The Arab Spring quickly came to represent an important event for political scientists studying the role of social media in politics. Mobilization theorists pointed to the back-to-back events of the Facebook Election and the Arab Spring to demonstrate that social media was visibly increasing political action.

Given the low rates of internet access in some countries where demonstrations erupted, however, cyber skeptics questioned whether the new media was really such a central tool or more like an additional asset for organizers.

Luckily, the online platforms also gave researchers access to a treasure trove of data on the demonstrations. The data paints a complex picture of the role of social media in the Arab Spring.

Through examining much of the political science research on the topic, one central theme becomes apparent – the role of social media in the protests varied greatly by context.

A study looking at the protests in the Gulf states, for instance, showed that there was a high level of social media activity, but a low level of in-person demonstrations.

Likewise, in Iran, demonstrations were dubbed the “Twitter Revolution” by Western media. However, there were only 8,600 Twitter users (out of a population of 70 million people) in the whole country at the time.

The (mis)perception that social media was driving the unrest, though, was so widespread that it may have steered foreign policy. The U.S. State Department reportedly requested that Twitter delay site maintenance which was scheduled during the unrest so as not to disrupt communication channels for organizers in Iran.

The Arab Spring was a complex social phenomenon and much research has been devoted to the topic. It would require many posts (maybe an entire website) to thoroughly examine the role of social media in each context. However, for the sake of a general understanding of how social media has influenced politics, it’s fair to say that social media was an asset for organizers but not likely a cause – and certainly not the sole driving factor as some had begun to believe.

Pippa Norris may have summarized the impacts of social media on the Arab Spring best in the book Electronic Democracy stating,

From the more skeptical perspective, therefore social media may function to sustain and facilitate collective action, but this is only one channel of communications amongst many, and processes of political communications cannot be regarded as a fundamental driver of unrest compared with many other structural factors, such as corruption, hardship, and repression.

Political Tools on Social Media: Change.org

Another prominent example of the internet’s impact on politics has been Change.org – a website that allows organizers to gather signatures for online petitions.

Change.org is it’s own website and differs slightly from social media as the site is exclusively devoted to online petitions. While many of the petitions are circulated heavily across social media, the site may be better categorized as ‘civic media’ or a ‘social action platform.’

Nonetheless, Change.org provides an important illustrative example of how online media platforms can directly impact politics. Their website claims at the time of writing this that over 37,500 of their petitions achieved the change they sought.

Victories from the website are across a range of issues from saving forests in the U.K. to implementing human trafficking regulations in Argentina to getting access to cancer treatments for a 32-year-old mother in Russia.

What started as an online tool in the U.S. has turned into a proven instrument for social change around the world. Change.org has become a staple tool for advocates everywhere with over 300 million actions taken by users in 196 countries.

Change.org is a classic example for mobilization theorists (or proponents of clicktivism) as it has been such a clear example of the change that simple online actions can bring.

Change.org’s model is not without its criticisms, however. One downside to the platform is that signatures can’t be identified and it is difficult to tell whether signatures are from the appropriate stakeholders or not.

For example, it may be difficult for a legislator or public official to tell if the signatures are from their district or somewhere else. Some officials have argued this point when resisting Change.org petitions.

Governor Christ Christie used this defense when justifying his refusal to sign an agricultural bill pertaining to the treatment of hogs in 2015. A petition supporting the bill received over 131,680 signatures. While it did not convince Christie to sign the bill, the petition did make the issue more publicly visible via media coverage.

Some have pointed to Change.org’s business model as a point of concern in and of itself. The website is operated as a business as opposed to being a nonprofit organization as many assume. Though, readers should note that Change.org is not a publicly-traded company and is not beholden to shareholders as some commentary suggests.

Critics have raised concerns over the fact that the platform sells emails and advertising space, which opponents fear will bring up conflicts of interest. Some have also accused the organization of allowing advertisers to “astroturf” or disguise the sponsors of ads to make it appear as if it were sponsored by local grassroots organizations.

The tension between ad revenue, the use of data, and a platform’s legitimacy is a chief challenge for all online platforms. Regardless of the criticisms leveled against Change.org, it is one of the most consistent examples of the impact that online media activity can have on politics and real lives.

Political Campaigns on Social Media: “El Bronco”

While “clicktivism” on social media can have fleeting results, evidence suggests that sites like Facebook can have sustained impacts on civic participation as well.

Researchers from Columbia University, for example, have argued that, at least in some cases, social media can effectively serve as the sole platform for political campaigns to engage supporters.

Researchers tracked over 750,000 posts and social media engagements between a candidate, Jaime Heliodoro Rodríguez Calderón (or “El Bronco”), and his supporters. The study tracked the engagements during and after the 2015 election for Governor of Nuevo León, Mexico.

El Bronco remained purposefully distant from traditional media before and after the election. He ran his campaign based almost exclusively on Facebook and online conversations with constituents.

Incredibly, El Bronco won the election by nearly 25 percentage points and researchers showed that his supporters maintained consistent and meaningful online engagement after his election.

For context, about 60% of households in Nuevo León have internet access (comparable rates to Mississippi, USA). Mexico also has a democratic government and has been consistently ranked as a ‘flawed democracy’ according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index. This environment no doubt shapes the community’s relationship with social media.

The research on “El Bronco” brings to light the fact that social media has a very localized impact. Despite the prevailing idea that the internet is the same everywhere, communities have formed very different relationships with social media and the internet more broadly.

The Columbia study pointed out that at least two main factors contribute to social media’s political impact in a community.

- First, a community’s type of government and political institutions will shape how social media platforms operate. In some places, social media may be free and developed by private institutions. In other places, social media is highly regulated and state-guided.

- Second, how a community produces, distributes, consumes, and regulates political news and information will shape how community members engage on social media. The United States is markedly different from the rest of the world in its news and politics; and, as such, we should be cautious of drawing conclusions for the rest of the world on research conducted in the U.S.

Researchers rightly pointed out that Facebook and the Internet are synonymous for many people around the world. Users everywhere, though, are developing a close relationship with the platform.

In 2016, Facebook representatives reported to the New York Times that users spend an average of fifty minutes a day on the platform. While fifty minutes may not sound like much, the average person spends about sixteen hours awake each day. That means that, on average, users spend 6.25% of their waking hours on Facebook.

The amount of time users spend on the platforms is an additional factor to the two mentioned above regarding social media’s impact on local politics. The more time a user spends on the platofrm the more information flows and, at the same time, the more data is generated on the user, which is used by campaigns for customized political messaging. The impact of individual usage, however, is not isolated to the user. Each individual engagement with the platform alters information flows even for community members who do not use the platform.

Starting a political or issue campaign? Check out our strategies, tips, and warnings for online campaigns.

“Slacktivism” – Cyber Skepticism

When online civic action began to emerge it also came with warnings from some political scientists that the web can be a double-edged sword. Some advocates even went so far as to make dramatic calls for grassroots reform and lament the death of social activism.

The main fear among some organizers and political scientists was that online civic action would amount to little real social change. Online civic engagement could give participants the sense that they had contributed to a movement, while in reality, the action was superficial and easy for those in power to ignore.

Cyber skeptics, then, speak of “slacktivists” instead of “clicktivists.” Sarah Kendzior captured public sentiment for the term for Al Jazeera:

Slacktivists are the hipsters of the digital world: everybody recognises them but no one claims to be one. The term likely predates the internet campaigns with which it is now associated – whereas once bumper stickers and buttons sufficed to show conviction, there are now groups to join, videos to share, causes to like, and other static virtual entities whose worth is calculated in clicks.

Campaigns that increase their visibility through viral content can generate public awareness and raise funds quickly, but they do seem to go through a public credibility test at a certain level of public recognition.

Below are two important examples of campaigns that are typically cited as being “slacktivist” movements.

Political Messages and Viral Trends on Social Media: Kony 2012

The Kony 2012 campaign is often pointed to as a textbook example of a “slacktivist” movement and it is worth taking a more detailed look at.

The campaign was created by Invisible Children – a nonprofit organization seeking to elevate the profile of Joseph Kony, an African warlord. The theory behind the campaign was that by elevating Joseph Kony’s profile it would aid in his capture, potentially even through Western military intervention.

Centering on a thirty-minute YouTube video, the campaign instructed supporters to post Kony 2012 material in their neighborhoods on a day in April that year.

The video struck an emotional chord with the public and it became a sensation within hours of posting. In just five days the video reached over 100 million views – making it the most viral video of YouTube at that time.

At first, the video generated mainly support from viewers and pleas for policymakers to take action. Public discussion, however, shifted dramatically after the first 24 hours. The next day critics more familiar with the situation surrounding Joseph Kony began to point out that the video over-simplified a complicated situation.

The campaign also received significant criticism for its portrayal of Ugandans as helpless and Americans as saviors. Several critics pointed out that the video relied on old footage and that the situation had improved in Uganda by the time the video was posted.

Some further accused the makers of perpetuating a “white savior industrial complex” – charity work that is hypocritical, superficial, and racially biased in methods of working.

The campaign fell apart less than two weeks after posting the video, though. Events culminated when the leader of the campaign suffered a mental breakdown. Social commentary was quick to open and quicker to close the book on the Kony 2012 phenomenon. But, while the criticisms of the campaign were valid, the Kony 2012 phenomenon likely had a mixed impact.

Despite rumors of money mismanagement, for example, the organization seems to have used its funds for their intended purposes. Invisible Children generated over 30 million dollars from the video alone and had also received grants for its work.

Some public figures have noted that Invisible Children had legitimate programs on the ground – despite their problematic framing of the conflict. The organization’s programs included “providing early warning systems to villages,” “support for local peace committees,” and “escapee support and reunification.” Invisible Children also successfully lobbied for the U.S. to send military advisors to Uganda to help find Joseph Kony. However, the U.S. had already sent military aid with questionable results. The campaign also briefly made Kony a household name fulfilling the stated goal of the initiative.

While the money from the video may have had positive impacts through supporting the organization’s programs, the video did not aid in the capture of Joseph Kony (who is still at large at the time of writing this).

Regardless of any benefits of the Kony 2012 video though, the execution and messaging of the campaign is an important case study for advocates. The primary lesson being that the story advocates tell needs to be accurate and, often, nuanced. Emotional appeals that lack substance can fall apart in the face of expert opinion.

Local Politics as a Global Social Media Discussion: #BringBackOurGirls

Other campaigns have fallen under similar criticisms to Kony 2012, but with different outcomes. The #BringBackOurGirls campaign emerged as a global social media trend after Boko Haram kidnapped hundreds of schoolgirls from Chibok, Nigeria in 2014.

The first use of the hashtag can be traced to a lawyer from Nigeria, Ibrahim Abdullahi, who may have been quoting a colleague’s speech.

The hashtag Abdullahi used in his tweet #BringBackOurGirls quickly became a social media phenomenon promoted by high profile figures and organizations such as Michele Obama, the Pope, Amnesty International, and UNICEF.

The movement suffered from the naturally short lifespan of social media trends, though, and critics pointed out that the return of the schoolgirls would not be a quick task. The campaign had also inadvertently given leverage to Boko Haram which used the high-profiles of the young girls to conduct drawn-out negotiations for their release. (Five years after the tweet, 107 had been released and 112 remained missing.)

Boko Haram, however, had kidnapped scores of youth and, in particular, young women prior to this instance. The size of the kidnapping in Chibok made the case particularly egregious and apparently well suited for social media trends.

The public’s focus on the one instance of kidnapping had other unintended consequences beyond giving Boko Haram leverage, though.

The mounting publicity also meant that those among the schoolgirls who were returned were treated differently than other youth who had been trafficked. The BBC reported that the Chibok girls (as they had become known) had not been allowed to return home and had strict limitations placed upon them after being rescued.

Another unfortunate side effect of the social media limelight was that other youth who were being trafficked had not received equal attention. Boko Haram had kidnapped over 7,000 young women and many young men in crises spanning years. However, only the case of the Chibok girls received a significant amount of outside support and attention.

Without the campaign though, authorities may not have taken action as quickly or at all. Crucially, the campaign had local support and was initiated by local voices. The spontaneous and uncoordinated nature of the #BringBackOurGirls social media trend also demonstrated the power of social media to act in emergency situations.

The entire initiative sparked from a single tweet that combined two key elements: 1) a crisis situation, and 2) a clear message – “bring back our girls.” Abdullahi’s tweet then took on a life of its own afterward. The results emanating from that single tweet show the potential in social media for raising awareness.

The Thin Line Between “Activism” and “Slacktivism”

Before moving on to the next section, it’s worth rounding out the debate on “clicktivism” vs. “slacktivism” because it’s the most common debate in the conversation around social media and politics.

The discussion above highlights the fact that it’s a blurry line between “activism” and “slacktivism.” Social media users can have an impact on politics; though, it’s tough to tell what type of impact participation will have on any given social cause.

Critics often point to the inconsistent and trendy nature of campaigns on social media as evidence of insincere participation. Being “slacktivist,” then, implies users are acting on social impulses and half-heartedly.

Many argue outright that online activists are naive and have little impact. However, criticisms are often based on anecdotes and incomplete examinations of social media’s impact on politics.

Research shows that social movements can draw exponential strength from typically unengaged users when they participate in viral social media campaigns.

While the campaigns themselves can be run problematically, it’s important that the phenomenon of “going viral” is separated from the conduct of any single campaign. In doing so, we can understand that there is power in social media trends and that it’s unfair to label all social media campaigns as being “slacktivist” or ineffectual and disingenuous.

Exciting research out of New York University in 2015 revealed a few important aspects of social media trends and political networks.

The study separated social networks into two parts – 1) the core, those who generate and/or regularly drive information sharing; and, 2) the periphery, casual participants in discussions and information sharing.

The study also looked at the way in which social networks spread information depending on the subject matter. For example, networks that shared news about protests or social causes behaved differently than networks that disseminated entertainment news.

Notably, networks that spread information about civic actions were just as reliant on the network periphery as the network core. The participation from casual users creates a collective impact that reaches beyond anything the core users of the network could create on their own.

The key difference between networks that spread civic information and networks geared toward entertainment news was the activity of the core. The core sustains a high level of activity in civic networks, while it provides very little of the overall activity in entertainment networks (meaning fans talk about celebrities more than celebrities talk about themselves).

The researchers concluded that that casual online supporters of social movements (those accused of being “slacktivists”) are critical in expanding the reach of campaign messages. The challenge is for organizers to harness the power of the periphery in meaningful ways.

“Big Brother Bubble” – Reinforcement Theories

The third set of theories around social media’s impact on politics can be broadly categorized as reinforcement theories or (as referred to on this website) the “big brother bubble.”

In the field of communications, reinforcement theories are concerned with all media – online and offline – and center on the idea that people seek information that confirms (or reinforces) their current world view.

Reinforcement theories can be taken further in the online context, though, to refer to the media’s potential to reinforce both individual world views as well as existing power structures more broadly. Studies looking at the behavior of networks on social media have revealed that, indeed, users divide themselves into online political communities with little contemplation of opposing views.

A 2011 study out of Indiana University, for instance, looked at the structures of Twitter networks and how their structures impacted information flows. Researchers found that users formed distinct communication patterns that isolated themselves within political camps.

The authors took the chance to echo previous warnings that political polarization can lead to more extreme views and damage a community’s “communication ecosystem.”

Social media is also increasingly raising alarm bells among watchdog groups and regulators for its role in government surveillance.

In 2019, the Brennan Center for Justice released a report which examined the way in which the U.S. government uses social media for surveillance. The report found that a number of U.S. federal agencies collect data on a range of things including political and religious views, physical and mental health, and the identity of family and friends.

According to the authors of the report, data sweeps by U.S. agencies like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have been ineffective at achieving their stated goals. Nonetheless, agencies continue to collect data, and reports indicate agencies sometimes focus on citizens opposing U.S. government policy.

For example, The Nation revealed in 2019 that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) collected data on protesters opposing Trump’s immigration policies as well as protesters opposing the National Rifle Association (NRA).

Outside of the U.S., some have raised concerns about the use of social media by governments to create overt citizen tracking systems.

Many alarm bells have been raised over China’s ‘social credit system’ – a Chinese state plan to monitor individuals and organizations in order to assign them a ‘social credit score’ based on behavior.

Experts have noted, though, that some media coverage of the online-based credit system has glossed over details and the current circumstances; many stories have depicted a fully operational system that is already in place.

The Chinese government currently collects alarmingly large amounts of data on many of its citizens, but the data is collected via a number of methods and isn’t currently aggregated, analyzed, and scored for every person.

Nonetheless, the amount and use of online surveillance currently taking place in the U.S., China, and around the world remains a growing concern among privacy rights advocates.

These examples of political polarization and state surveillance reveal that social media has introduced opposing forces into politics. For example, polarization and surveillance on social media are directly opposed to the increase in communication channels and civic participation also enabled by the platforms.

The remaining portion of this section examines more background and examples of social media reinforcing existing power structures and political polarization.

Internet Freedoms in the Global Context

A 2019 report by Freedom House, an independent watchdog organization, gave a comprehensive and global overview of how social media is used for political purposes. The data used in the study represent 87% of internet users worldwide.

The report highlighted three primary ways in which governments and political regimes manipulate social media.

- Informational measures allow governments to interfere with online discussions or with the flow of information.

- Technical measures allow governments to restrict access to the internet or websites.

- Legal measures allow regimes to prosecute political opponents for online speech or behavior.

Authors noted that 38 out of the 65 examined countries saw the spread of politically-motivated misinformation. The report also found that 59% of the analyzed countries had instances in which the government “deployed progovernment commentators to manipulate online discussions.”

National governments in 56% of the countries discussed in the report blocked political, social, or religious content; in 46% of the countries, the government had disconnected internet and/or mobile networks for political reasons.

The use of legal measures has increased over the years as well, and researchers found that 47 countries recorded arrests of social media users for political, social, or religious speech.

Alarmingly, the study also revealed that nearly 3 billion people (or 89% of internet users) are being monitored by social media surveillance programs. Forty countries were found to have instituted advanced government programs to collect and analyze social media data.

One conclusion of the report is that social media restrictions erode other rights as well. The authors argue that that the violation of privacy rights then leads to discrimination as well as restrictions to speech and assembly, which in turn erodes institutions and the rule of law.

Surveillance Capabilities: XKeyscore

Perhaps the most extreme example of online government surveillance is the XKeyscore program revealed by Edward Snowden. The program is a computer system used by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) to collect and analyze global internet and communications data.

The XKeyscore program goes far beyond social media surveillance, however. The program represents the most advanced capabilities in online government monitoring and is the ‘poster child’ for reinforcement theories.

By some accounts, users of the XKeyscore program can see virtually everything an individual does online including emails, browser history, and metadata. The system also collects data beyond internet use – including phone calls, video messages, and even faxes.

The Intercept reported in 2015 that virtually no data escapes the eyes of XKeyscore users. Beyond emails the program also collects:

“pictures, documents, voice calls, webcam photos, web searches, advertising analytics traffic, social media traffic, botnet traffic, logged keystrokes, computer network exploitation (CNE) targeting, intercepted username and password pairs, file uploads to online services, Skype sessions and more.

A series of revelations about the XKeyscore program demonstrated the power of U.S. intelligence agencies to even keep tabs on other world leaders.

Uncovered documents show U.S. intelligence officers used the program to spy on UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to retrieve his talking points before a meeting with Obama.

Later discoveries from the leaked documents exposed U.S. spying on the leader of a close ally – the German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Reports also suggest that the U.S. intelligence agencies surveilled a German media outlet – Der Spiegel, causing concern among critics that the U.S. was interfering with free press abroad.

The program is not only used to spy on high-profile targets for certain pieces of information either. Some have pointed out that the system is automated to track people who trigger certain conditions.

Analysts who took the time to sort through the program’s source code made public by Snowden noted that the NSA specifically targeted people looking for privacy software. A group of German analysts reported that XKeyscore is programmed to start tracking anyone who searchers the term ‘privacy software.’

With regards to social media specifically, leaked training materials for the program calls social media “a great starting point” for surveillance methods. Given the sheer volume of exchanges and activity on social media, it stands to reason that even the most advanced online surveillance programs begin with data from these platforms.

XKeyscore likely represents the most sophisticated means of surveillance currently known to the public. The program is extensive and many resources have been dedicated to the topic. For our purposes of understanding the impact of social media on politics, the XKeyscore program shows that no information on social media platforms is private and it can likely be retrieved by one or more government surveillance programs.

Political Marketing and Privacy: The Case of Cambridge Analytica

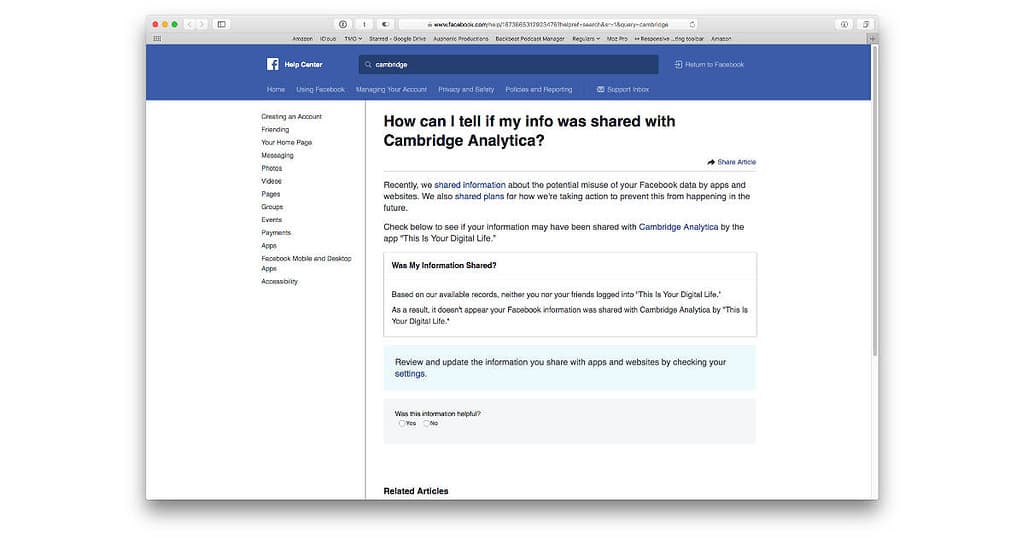

While XKeyscore demonstrates the capabilities of national governments to spy on users, the Cambridge Analytica scandal brought to light what type of data actors are able to retrieve on users.

Cambridge Analytica, a consulting firm hired by the Trump campaign, harvested data from over 87 million Facebook users by creating a quiz that not only acquired the data of those who took the quiz, but also the data of their ‘friends’ on the platform.

The firm used the data to target political ad campaigns in clear violation of Facebook’s policies. Documents later showed that Facebook was aware of the breach and failed to take action.

Some commentators pointed out that the firm may not have been able to make much use of the data, however. Cambridge Analytica had a dubious reputation in Washington for lacking follow through on their innovations and the data from the leak didn’t appear to be acted upon. As such, the breach was not likely a deciding factor in the election.

Ironically, the firm may have had some effective data analysis techniques. The group’s primary technique provided a scale to classify individuals along a spectrum of how open, conscientious, extroverted, agreeable, and neurotic they are.

The technique (deemed OCEAN) was publicized as a groundbreaking innovation and provides an important example of how user data can be assessed by political campaigns. Wired magazine even named the group’s CEO, Alexander Nix, one of 25 Geniuses Who Are Creating the Future of Business in 2016 for the technique.

Reports have also surfaced that Cambridge Analytica was involved with a group called Leave.EU to promote the Brexit campaign in 2016 as well. While the two groups did not have a formal contract, evidence suggests that Cambridge Analytica provided Leave.EU with datasets on potential voters.

Social media data, then, has become an increasingly natural target for firms hired by political campaigns. Data, as accumulated by sites like Facebook, give firms the ability to target users with messages that confirms users’ biases and stokes political hostility.

The case of Cambridge Analytica also shows how political reconnaissance can resemble state surveillance and contribute to political polarization.

Politics and Social Media Access: Sudan’s 2019 Protests

The 2019 Freedom House report discussed above found that 30 out of the 65 countries that were examined (or 46%) blocked access to social media for political purposes.

In Sudan, for example, social media sites were disabled in an attempt to quell demonstrations in the capital, Khartoum. From the winter of 2018 to the summer of 2019, protestors demanded democratic elections and an end to the regime of President Omar al-Bashir.

Al-Bashir, who had ruled over the country for thirty years, responded to protests with physical violence and online censorship.

Social media sites were, at times, specifically blocked in an effort to disrupt information flows. At other times, the internet was disabled entirety. Ultimately though, the protests succeeded in ousting Omar al-Bashir without consistent internet access.

For context, 29% of Sudan’s population (11.8 million) has access to the internet and only 7% of the population (2.8 million) uses social media. While only a small percentage of the population was impacted by internet blockages, it’s likely that many of the protestors were among the impacted users.

The ousting of Omar al-Bashir shows that social media and internet interruptions will not fatally disrupt information flows for organized social movements. Nonetheless, the tactic is being used at an increasing rate by governments around the world.

Access Now’s internet shutdown tracker shows that from 2016 to 2018 incidents of internet shutdowns rose by 250% worldwide – from 75 incidents in 2016 to 188 incidents in 2018.

Shutdowns have become so frequent that NetBlocks, a private organization working on digital rights and security, developed a tool to determine the cost of internet shutdowns to the economy of any country in the world.

In the case of Sudan’s protests, for instance, internet shutdowns for five days alone cost the Sudanese economy $228,924,285; a significant amount considering the protests began over high prices and shortages of basic goods.

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) argues that internet shutdowns have lasting impacts on the economy long after access is restored. In a milestone report, Framework for Calculating the Economic Impact of Internet Disruptions in Sub-Saharan Africa, the group argues:

The economic costs of an internet disruption persist far beyond the days on which the disruption occurs. Indeed, the negative effects of a disruption on the economy may extend for months, because network disruptions unsettle supply chains and have systemic effects harming efficiency throughout the economy. These longer-term effects are not limited to the immediate ICT ecosystem: factors such as investor confidence and risk premiums can affect a country’s broader economy long after the disruption has been lifted.

Political Censorship and “Fake News” on Social Media

Online access and censorship are often discussed as part of the same phenomenon. However, there are distinct differences and important reasons to examine each issue separately.

The definition of ‘social media (or online) censorship’ can vary from organization to organization and researcher to researcher. For our purposes here we will define ‘censorship’ as the manipulation of information flows – as opposed to restrictions in access which are blockages to information flows.

In other words, censorship has to do with the content of expression whereas access issues are concerned with the medium of expression.

In some cases of online censorship, governments may simply block certain content related to politically sensitive issues. Critics have even accused some social media platforms of collaborating with governments to censor content.

In 2017, for example, Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident who took up asylum in Canada, started a hashtag critical of a Saudi official – Turki Al al-Sheikh, head of the Saudi General Sport Authority.

The hashtag quickly took off with over 6,000 tweets in less than 15 minutes. Then suddenly, all mentions of the hashtag vanished. Users reportedly questioned Twitter over the incident but never received a response. The silence left some to speculate whether the company was complicit in the action or whether it had been hacked and was wary of revealing politically sensitive vulnerabilities.

The incident is not unique, though, and demonstrates the power of governments to control information over the internet even outside of their national boundaries.

Deleting social media posts, however, is a heavy-handed way for governments to censor information. In most cases, such major deletions are reported in the media and damage not only the reputation of the government behind the censorship but, also, the tech companies responsible for the platform.

Other methods of censorship have emerged in the social media era that are much more subtle. For instance, student researchers at the University of California Berkeley and the International Computer Science Institute found that Russia had employed spamming techniques on social media for political purposes during the country’s 2011 parliamentary elections.

Following the elections, supporters of the losing party organized rallies at Moscow’s Triumfalnaya Square. Demonstrators gained traction online by using the hashtag #Triumfalnaya.

Russian government forces responded with bots that posted content using the same hashtag, but with contradictory messages in order to suppress and confuse the online conversation. According to the student researchers, the Russian political spamming effort involved 25,860 fraudulent accounts which sent 440,793 tweets

This censorship tactic of ‘drowning out the opposition’s voice’ is increasingly popular among political regimes and organizations. More subtle than deleting content or blocking access to accounts, this technique is likely being developed further by these actors.

“Fake News” and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

One of the most famous incidents of manipulating information flows over social media is from the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, which solidified the phrase “fake news” as a household term.

The phenomenon of “fake news” is not new or unique to social media though. The dissemination of misinformation likely goes back to the beginnings of mass media. (As far back as 1835, for example, the New York Sun published a series of articles suggesting that scientists discovered life on the moon, called the “Great Moon Hoax” today.)

However, the spread of misinformation represents a much larger issue online than it ever had in print media. The ease with which individuals can set up websites, distribute false information, and even profit from it not only increases the chances that “fake news” will spread but also incentives the creation of false news stories.

Evidence also suggests that the public’s trust in traditional media outlets is declining, adding to users’ reliance on social media for news. To make matters worse, the increasing political polarization may be impacting users’ ability to objectively assess news stories.

Misinformation on social media, then, can accelerate political polarization. A report from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) found that false stories spread faster and farther than true stories. As such, political tensions can be stoked with little relative effort and resources on social media.

The authors of the report note that the difference may be explained by the fact that novel information spreads faster and farther than everyday news. In other words, “fake news,” which often has jarring headlines, appears to be novel information to many users, accounting for its rapid consumption and dissemination.

Notably, the authors found that false news stories spread faster and farther than the truth in many categories such as natural disasters and terrorist attacks. Yet, the effect was most pronounced for political misinformation.

Contrary to popular assumptions, the study also found that robots were not the primary culprit for the spread of misinformation. Researchers found that humans were primarily responsible for the exaggerated spread of misinformation; robots treated true and false articles in the same manner.

With respect to the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, so many false stories were spread that there was confusion over who or what was producing the content. Three primary sources appear to account for the misinformation: 1) passionate Trump supporters, 2) bloggers seeking to make money off of visitors to their sites, and 3) Russian intelligence and propaganda organs.

The impact of “fake news” on voter choice is difficult to assess, but studies have looked at various aspects of the phenomenon. For example, a study published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives concluded that the average U.S. adult was only exposed to about 1.14 “fake news” stories throughout the 2016 election season.

The authors note that if one false story had the same impact as a television commercial on voter choice, then all the false stories analyzed in the study would have impacted voter choice by hundredths of a percentage point; a figure too insignificant to determine the election outcome.

On the other hand, a study out of Ohio State University found that “fake news” articles may have influenced a small but important segment of the voter population – voters who voted for Obama previously who then went on to vote for Trump in 2016. The study found a strong correlation between believing “fake news” stories and defection from the Democratic ticket.

The authors of the Ohio State University study caution readers from drawing too many conclusions as the correlation does not equal causation. In other words, factors that prompted voters to defect may have been different from the factors that caused them to believe the false stories.

Many news outlets conducted interviews of this segment of voters after the elections and found many reasons for their voting behavior. Some interviews suggest voters made up their minds long before they had the chance to encounter “fake news.”

Another telling example of voter motivations can be found in a focus group conducted by the Roosevelt Institute and the Democracy Corps which looked at voter motivations in Macomb County, Michigan. The county is in a key swing district and offers insights into the mindset of the Obama-Trump voters (as they have become known).

The results of the focus group suggest that this small section of the electorate had many motivations that were often rooted in local issues or the desire to see sweeping change in Washington.

All the above reports and studies, taken together, suggest that “fake news” was a complicating factor in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, but it was not likely the determining factor. Nonetheless, the spread of misinformation clearly has serious implications in politics, governance, and public welfare.

“Fake News,” Freedom of Speech, and Government Censorship

With the spread of misinformation increasing online, regulators around the world are beginning to examine laws and policies that would attempt to stop false stories from spreading. These attempts at addressing the issue are opening up serious questions between freedom of speech and government censorship.

Contrary to the examples discussed above where governments are censoring content in order to suppress opposing political views, officials elsewhere are attempting to curb the deliberate spread of misinformation in the realm of public health and safety.

In the United Kingdom, for example, regulators have begun debating the merits of holding tech firms such as Facebook and Google responsible for the spread of false health-related claims.

U.K. officials have become increasingly concerned about the spread of misinformation that claims vaccinations cause autism, a claim not supported by the health and scientific community. Regulators are suggesting that the spread of this misinformation has had noticeable impacts on the health of the country.

One indication of that is that the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared Britain measles-free in 2016. Just two years later, infections of the disease ballooned to 991 in the country. Some policymakers point to the spread of misinformation as a major reason for the disease’s resurgence.

Some are calling for an entirely new regulatory body. The proposal is to have the agency enforce restrictions on issues such as child pornography and promoting terrorism as well as such general topics like hate, misogyny, and the glamourization of suicide.

Other countries too are beginning to put serious regulations on tech firms for the content on their platforms. In Australia, lawmakers passed new measures in 2019 after an attack on a New Zealand mosque in which the attacker posted the incident on social media. The content lingered for some time after the attack, prompting concerns among officials.

The measures passed in Australia impose steep penalties on tech companies if they fail to quickly remove ‘abhorrent content.’ The new regulations could (theoretically) mean jail time for executives of tech companies that are out of compliance.

In India, draft policies unveiled in December 2018 sketched out plans that would force tech firms to self-regulate and remove inappropriate content from their platforms. The policies included a range of measures that would weaken users’ privacy and potentially lay the foundation for automated censorship.

Some have raised concerns over the idea of automated filters on social media websites suggesting that it cedes rights to freedom of speech and privacy. Such a system could also open the door to abuses by political regimes.

Political Interactions and Harassment on Social Media

Online harassment (also known as “cyberbullying”) has also become a serious issue over the past decade. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center poll, 4 in 10 U.S. citizens had faced online harassment at the time, and 62% of respondents said the issue was a major problem. The data also suggested that the most common type of online harassment Americans faced at the time was political in nature.

Despite the widespread perception that online harassment is a growing problem, the issue has not been studied as closely as the other aspects of social media’s impact on politics.

Harassment is not often discussed alongside online surveillance, censorship, and other ways in which social media reinforces power structures. However, online harassment and the way in which users engage in political discussions likely reflects, facilitates, and exaggerates power structures.

In 2016, at the height of the contentious U.S. presidential election season, Pew conducted a poll to gauge public opinion of online political interactions. Pollsters reported a number of key points:

- 37% of Americans were “worn out” by online political interactions; 20% of Americans said they enjoyed online political engagement.

- 59% of respondents found interactions with users who held opposing political views as stressful and frustrating; 35% found them interesting and informative.

- Half of all Americans (49%) thought that political discussions were angrier on social media than in other formats.

- 41% of Americans had been subjected to offense name-calling online. About one in five Americans (18%) had been targets of severe harassment such as “stalking, physical threats, sexual harassment or harassment over a sustained period of time.”

One obvious takeaway is that political interactions online (and offline) can be a mixed bag – exhausting some users while energizing others; given space to some, while making others targets

Politicians, Free Speech, and Harassment on Social Media

Perhaps unsurprisingly, politicians themselves are often the targets of social media harassment. A study out of the University of Toronto, for instance, provides some insights into what politicians face on the platforms.

Researchers looked at public messages sent over Twitter to 195 Canadian politicians and 100 U. S. Senators. The study found that 10.6% of public messages toward Canadian politicians were “uncivil,” and 15.4% of public messages towards U.S. Senators were “uncivil.”

The study concluded that male politicians received slightly higher rates of insulting messages on average than their female colleagues in both the U.S and Canada. While these findings may seem counter to public perceptions, it is consistent with other data discussed in this post (see Pew 2016 and 2017 polls for more).

The study, however, also found that harassment was conditional on visibility and gender. The data reveals that female politicians who had received a higher-than-average level of public recognition received more “uncivil” messages than their male counterparts.

Social media has opened up a new, rapid, and public communication channel between constituents and public officials. For the most part, that’s a good thing and this type of engagement can increase public trust in officials and government institutions.

Unfortunately for public officials, the new mode of communication has also allowed for higher volumes of unproductive and harassing messages. Elected officials have even begun to face scrutiny for blocking users on social media who send unwanted messages.

Starting in 2017 a series of U.S. politicians were highlighted in the press for blocking social media users. The politicians outed in the media have ranged the political spectrum from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Kamala Harris to U.S. Maryland Governor Larry Hogan and President Donald Trump.

The issue has gone beyond the blocking of online harassers. One Minneapolis City Council member, Alondra Cano, for instance, reportedly blocked two journalists over unflattering stories. The move has prompted a new city initiative that would institute certain controls on public accounts.

Certain cases of blocking have even given rise to their own social media hashtags. Kentucky Democrats famously keep a running list of all the people blocked by Governor Matt Bevin, using the hashtag #BevinBlocked.

The issue of politicians blocking users became so prevalent that it reached U.S. courts. In 2017, a group of Twitter users sued Trump for blocking them on the platform. The courts ruled that politicians were not allowed to block social media users because it violated users’ freedom of speech rights.

Rulings have referred to social media platforms as the “modern public forum” and, thus, users’ ability to access the accounts of public officials fall under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Children have also faced harassment over social media for political reasons. In one instance, parents who ran a social media account of their child mimicking U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez temporarily closed the parody accounts due to reported harassment.

The parents said that their daughter, known as Mini AOC online, had become the target of increasingly dark attacks. The account was later reinstated, but has had other instances of being suspended by Twitter for attempting to “manipulate the conversation.”

Similarly, Greta Thunberg, a 13-year-old Swedish climate activist, was the center of heated public discussion over cyberbullying in 2019. After Thunberg delivered a speech at the UN, U.S. President Trump tweeted at her in what critics saw as a sarcastic jab at the 13-year-old activist after her impassioned speech.

Aggressive tweets from the President continued after the initial jabs. Social media critics pointed out the exchanges were further problematic in light of Melania Trump’s #BeBest campaign – an initiative partly aimed at combatting cyberbullying among children.

Politics, Identity, and Social Media

When politics and identity meet on social media, public discourse and conflict can be magnified. The event can be simultaneously disenfranchising and empowering for whole communities.

For example, the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network released a report in 2013 looking at online bullying and LGBT youth. The Network discovered that while LGBT youth experienced more online bullying than their straight peers, LGBT youth also had better online support networks, were more adept at utilizing online healthcare support, and were more civically engaged than their peers.

The intersection of politics, identity, and social media is a rich topic and much of it remains to be explored by researchers. Below are just a few examples of cases at this intersection.

Starting a political or issue campaign? Check out our recommended resources to get started online.

Politics, Gender, and Social Media: The #MeToo Movement

In a Pew 2017 poll men were twice as likely to be harassed for their political views than women in the U.S. at the time. Women, however, were twice as likely as men to be targeted on social media for their gender.

Female political candidates appear to face particularly egregious and consistent forms of harassment. A 2016 Inter-Parliamentary Union survey of 55 women members of parliament (MPs) from 39 countries stated that 44% of women MPs “received threats of death, rape, beatings or abduction during their parliamentary terms, including threats to kidnap or kill their children.”

Researchers noted that social media was the primary way female politicians received harassing messages. One MP noted that she received over 500 threats of rape on Twitter in just four days. In some cases, online threats caused women to withdraw from politics. In other cases, social media users obtained private pictures or manipulated photos of female politicians to create explicit and demeaning content.

While social media has opened up more channels for sexual and gender-based harassment, it has also presented opportunities for education and advocacy campaigns.

The #MeToo movement has become one of the most widespread social media movements of all time. The movement has its roots as early as 1997 when its creator, Tarana Burke, encountered a sexual abuse victim. Later, in 2006, Burke created a page dedicated to the issue on MySpace.com.

However, it wasn’t until eleven years later that the movement took off on Twitter when actress Alyssa Milano retweeted a post from Burke. The post asked victims of sexual assault to reply “me too” in an effort to demonstrate the scale of the issue.

The hashtag went viral instantly after Milano’s tweet. It reached over 85 countries and was mentioned in 1.7 million tweets worldwide in just ten days. Facebook reported 12 million posts and 4.7 million people participating in the conversation in the first 24 hours alone. The conversation was so pervasive that at the end of those ten days an emoji was developed to denote the campaign.

Just one month after the viral posting, legislation was introduced by Representative Jackie Speier in the U.S. Congress inspired by the movement. Called the ME TOO Congress Act, the bill was designed to make it easier to report, investigate, and resolve allegations of sexual misconduct in Congress. The bill, however, was never enacted.

Within a year, though, the movement was responsible for removing at least 201 men accused of misconduct from significant positions of power in the U.S. alone. Those 201 men alone accounted for the experiences of at least 920 individuals who came forward with allegations.

Internationally, the movement sparked major waves of allegations and, in some cases, dismissals and resignations. In the U.K., for example, allegations swept Westminster implicating at least 36 members of parliament.

The movement even proved responsive to state censorship. In China, the hashtag gradually became censored by state authorities. Social media users coped by using #RiceBunny instead of #MeToo. In Mandarin, the words for “rice” and “bunny” sound like “mi” and “tu.” Users also used the combination of a rice emoji and a bunny emoji to signify the movement.

The #MeToo movement, though, is not without its problems and criticisms. Some noted that the movement may have had unintended consequences.

Human resource professionals cautioned that while the movement created a safer environment for people to come forward with allegations of sexual misconduct, it also may have had the unfortunate side effect of reducing opportunities for women.

For example, some were concerned that males would be less likely to invite their female counterparts to informal networking opportunities like office happy hours. Others raised concerns that appropriate behavior varied greatly by region and that the movement was enforcing a certain progressive standard on local contexts.

The movement has also re-opened serious questions around gender, race, and class. Burke herself, at times, called attention to the fact that the movement had forgotten poor women of color and had been appropriated in many respects by middle and upper-class white women.

Burke has noted that the movement was originally created to help survivors of sexual harassment with particular respect to black and brown girls. The movement, as Burke points out, gradually grew to include all genders and victims of sexual harassment. Currently, the movement’s purpose is to provide both resources for healing and tools for advocates.

Criticism notwithstanding, the social media hashtag has had a significant number of real-world implications. A few significant examples of changes to law or policy include:

- Reforming nondisclosure acts in California, New York, and New Jersey (which prevented some from speaking out about misconduct),

- Inspiring measures in New York and California to extend protections to independent contractors, and

- Helping to raise over $24 million for legal fees for those who couldn’t afford to take legal action against harassers.

Politics, Race, and Social Media: #BlackLivesMatter

In the year following the election of U.S. President Obama, research from Howard University noted that African Americans perceived a decrease in discrimination and consequently saw an increase in opportunities. Yet, economic statistics indicated that black Americans had a worse year relative to other demographics.

The report also indicated that white conservatives were more likely to see the election as a sign of improving race relations than were white progressive voters. Researchers noted that except for a small portion of the electorate there was a prevalent notion that the U.S. had entered a “post-racial” world.

Despite these perceptions, the years following Obama’s inauguration saw a dramatic increase in hate speech and hate groups on social media. A study out of Baylor University demonstrated that the increase in online racial aggression also led to the resurgence and spread of historically stereotypical depictions of African Americans.

In 2017, just eight years after Obama took office, the Pew Research Center reported that 1 in 4 African Americans had been subjected to online harassment for their race or ethnicity – higher than any other racial group. By contrast, 1 in 10 Hispanics and 3% of white Americans faced racially-motivated harassment at the time.

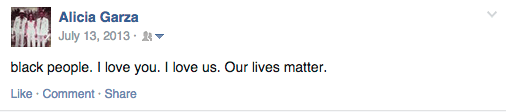

Perhaps the most indicative example of the intersection of race, politics, and social media is the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement. Born from a simple Facebook post in 2013 from Alicia Garza, an American civil rights activist, the comment spun off into a full-fledged movement. The movement has become one of the most well-known U.S. advocacy campaigns of the modern era.

Garza posted a series of comments afterward that she later termed a “Love Letter to Black People” following the acquittal of George Zimmerman who had been charged with the second-degree murder for the death of Travyon Martin in Florida.

The BLM online conversation differed from other movements discussed above such as the #BringBackOurGirls campaign in several key respects. First, the movement was deliberately designed by activists. While Garza’s Facebook post was genuinely spontaneous, the activist later met with her colleagues to discuss a coordinated campaign in which she drew inspiration from her posts.

Second, the hashtag sustained local attention in the U.S. and was adaptable to local conditions elsewhere. The #BringBackOurGirls campaign, on the other hand, had been removed from its local context of Nigeria, giving more voice to influencers instead of impacted communities.

Third, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag addresses an underlying issue of racial violence and marginalization whereas the #BringBackOurGirls campaign focused on one instance of a larger issue. Because the #BlackLivesMatter campaign addresses a long term issue the hashtag supporters likely understand from the outset that the movement requires longevity, giving the movement a resilient and stable social media following.

Critically, #BlackLivesMatter has managed to focus public discussion on the topic of racial injustice and introduce important debates in public discourse. One manifestation of the campaign’s impact on the U.S. national discussion around race was the counter phenomenon of “All Lives Matter” (or #AllLivesMatter) which was largely seen as a critique of the BLM movement for elevating black lives above all others.

The counter phrase, “All Lives Matter,” was echoed by a number of public figures including Tim Scott, Richard Sherman, Donald Trump, Ben Carson. Notable Democrats too, like Nancy Pelosi, and Hillary Clinton, have promoted the phrase.

BLM activists responded that the hashtag is not meant to suggest that black lives are more important than other lives; the campaign is meant to draw attention to the fact that black lives are significantly more insecure than the lives of white Americans.

Supporters of the BLM movement offer statistics such as black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white men in the U.S. Or, that black women are about 2 to 3 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women in the U.S.

BLM supporters also began generating a flurry of social media illustrations of the movement’s purpose to counter the “All Lives Matter” critique.

The BLM campaign’s high-profile may have even made it a target of geopolitical exploitation. Russian agents, for example, have been accused of mimicking BLM social media accounts on Facebook in order to stoke racial hostility in the U.S. For a time, the fake Russian accounts even had more likes than the official BLM account. The problem has become so widespread that the BLM movement created an initiative to combat misinformation in 2020.

Politics, Faith, and Social Media: Antisemitism in Europe

The connection between politics, religion, and social media harassment is another area of emerging interest and concern. For example, data from a 2018 survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) may reveal linkages between increases in social media harassment and socio-political trends around religious intolerance.

FRA surveyors examined a sample population that was representative of 96% of Europe’s Jewish population. In the survey, 89% of respondents reported an increase in antisemitism in their country and 85% considered it a “serious problem.”

Respondents, on average, rated anti-semitism as the biggest social or political problem they faced in their countries. Almost 9 in 10 (89%) of respondents identified social media as the primary means in which they saw the spread of antisemitic content.

Demonstrating the point, in the fall of 2019 a Holocaust survivor and Italian Senator-for-life, Lilliana Segre, was put under police protection after she began receiving 200 threats a day on social media. Segre, who was sent to Auschwitz at the age of 13, responded to the online threats by establishing a parliamentary committee to combat hate, racism, and anti-Semitism.

Citing concerns over freedom of speech and the committee’s failure to address “the role of Islamic extremism,” Italy’s center-right party (Forza Italia), far-right party (Brothers of Italy), and “eurosceptic” party (League Party) all abstained from voting on Segre’s committee to combat hate, racism, and antisemitism. Commenters noted that it marked the first time since World War II the national consensus failed to reflect religious tolerance.

In addition to antisemitism in Europe, other regions have seen anecdotal evidence of tensions. However, without much sociological data, trends in some countries can be difficult to properly assess.

Myanmar, for example, has seen incidents of hate and violence against Muslims spread over social media with devastating consequences for communities. The spread of online religious intolerance is likely increasing and, as such, more data and analysis are needed to grapple with the issue.

Are You Conducting a Political Campaign on Social Media? Check out our recommended resources for getting started online.