Community organizing is a more well-defined term than related phrases like grassroots activism or even civic engagement.

Community organizing is a process of building power through collective action in order to address shared grievances or advance shared interests. Organizing of this sort is characterized by an emphasis on power relations and aligning interests. Conflict and negotiation tactics, then, are fundamental.

Compared to other related terms like community involvement and grassroots activism, community organizing has a more theoretical underpinning. That’s not to say that it doesn’t have an impact on the real world – it does and has been proven effective time and time again.

But, the term also comes with a rich literature that poses important questions about power, ethics, confrontation, strategy, and more.

Community organizers should be prepared to engage in some basic philosophical discussions before getting started. The most important concepts to explore are how to build power and align interests.

It’s important to note that community organizing must grow out of shared interests and can’t be done on behalf of an impacted community like advocacy. Organizers, like advocates though, must be versatile and understand both how to inspire collective action as well as how to make the change they seek within an institution or society.

That can sound like a tall order, but it has been done countless times throughout history. I have no doubt that community organizing victories are happening every day all around the world. Organizing can be a difficult journey, but it can also be exciting, educational, and immensely rewarding.

Below, this post dives into basic understandings of community organizing, exploring both power relations and interests.

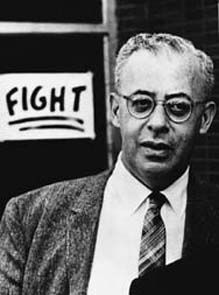

The “Freud of Community Organizing”

It’s difficult to talk about community organizing without mentioning the name Saul Alinsky. Alinksy is one of the most authoritative voices on the subject and his work has inspired figures across the political spectrum.

Alinsky made a name for himself as an activist in Chicago. One of his early victories came as he organized communities that were hostile to each other in the Back of the Yards neighborhood of Chicago. The area was the subject of Upton Sinclaire’s famous novel The Jungle, which depicted the severe poverty and exploitation of immigrants living in the neighborhood at the time. Alinsky was able to unite the various ethnic communities in the area such as Irish, Poles, Lithuanians, Mexicans, Croats and African Americans into a united front that won important concessions from local businesses, landowners, and the city government.

While Alinsky was an activist, he was also an important political theorist. His most popular (and probably most important) work was his book Rules for Radicals. The book is meant to be a guide on how to create a successful community-led movement.

For Alinsky, organizing is all about how the Have Nots take power from the Haves. His writing is in the realm of the realpolitik and offers organizers raw wisdom from important moments in his career. Much of his work focuses on how to approach confrontation and when to seek compromise. While readers may not agree with everything Alinsky wrote or did, it’s no doubt imperative to start an organizer’s education with Rules for Radicals.

Some have even commented that “Alinsky is to community organizing as Freud is to analysis.” However, unlike Freud, Alinksy’s work had two distinct components – one as a political theorist and the other as a radical progressive activist.

It’s worth noting that Alinsky’s work – as it relates to theory – has influenced both progressive and conservative movements. Movements ranging from the Tea Party to Occupy Wall Street have used principles and strategies taken directly from his work. Conservatives have even tried to subtract Alinksky’s theories from his politics altogether in such books as Rules for Patriots.

His political legacy is much more complex, however. Alinksy had a reputation for abrasive tactics and became the archetype of radical leftists for many conservatives. He was such a force of his era that both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama had been shaped by his legacy in different ways. Though, both ultimately disagreed with Alinksy in his thinking that power lay principally with the grassroots and outside of institutions.

Regardless of Alinsky’s political legacy, his work remains important material for organizers and theorists today. The concepts and ideas in his work are fundamental – not because they represent an ultimate truth or final world but because they represent a necessary starting point for those working toward social change.

A Note on Summaries of Rules for Radicals

Alinksy’s work has been dissected by many, many political theorists over the years. As in similar cases, there is some disagreement over his theories and what his work was truly trying to convey. In fact, he famously recounts a story in Rules for Radicals in which he anonymously took a university political science test. Several questions asked about the intentions and interpretations of Alinksy’s work. The professor marked Alinksy’s answers wrong to these questions. In other words, the professor did not accept Alinksy’s own explanation of his work.

It goes without saying then that you can find scores of explanations which vary greatly from one writer to the next. While each theorist is entitled to their own opinion, readers should be vigilant as the book is very often misrepresented (both intentionally and unintentionally).

A quick search for “Rules for Radicals” brings up articles that boil his work down to 10, 11, 12 or 13 rules. Yet, Alinsky lays out several sets of rules for different subjects such as ethics and tactics. Tellingly, many popular articles on the book even misrepresent the number of chapters (there are nine chapters and one prologue) – begging the question of whether the authors have really read the book or only read about the book.

All this is worth saying (especially in the spirit of Alinsky’s writing) because readers should not take the descriptions on this page as the only way to understand his theory. I’ve tried to distill things as objectively as possible, but there is much more to be said and readers will need to draw their own conclusions.

Alinsky’s Theory of Community Organizing

Central to Alinsky’s work and much of modern theory around community organizing are the two notions of self-interest and power. For Alinsky and many others, self-interest is the currency of organizers and amassing power is the aim.

Self-interest plays a role in every step of the organizing process. Starting with the motivations of the organizers and the individuals being organized; no community will take action until self-interests are activated and aligned enough for individuals to begin supporting one another. Later on, of course, the self-interests of those in power come into play – but not before the Have Nots (as Alinsky refers to them) are brought together over common goals.

Despite depictions to the contrary, Alinsky does not suggest that every interest must be met and that the whole process is a selfish endeavor. On the contrary, he repeatedly stresses the need for compromise and the importance of letting the organizing process unfold democratically. He writes in the prologue,

From the beginning the weakness as well as the strength of the democratic ideal has been the people. People cannot be free unless they are willing to sacrifice some of their interest to guarantee the freedom of others. The price of democracy is the ongoing pursuit of the common good by all of the people. One hundred and thirty-five years ago Tocqueville gravely warned that unless individual citizens were regularly involved in the action of governing themselves, self-government would pass from the scene. Citizen participation is the animating spirit and force in a society predicated on voluntarism.

After communities (or the Have Nots) are brought together, organizers must identify the self-interests of those in power and ways by which those interests can be transformed to meet the demands of the people.

Alinsky makes clear though that in many cases the power to change a situation may be diffuse and no one individual will be able to change the circumstances. In some cases, Alinksy notes, communities even bring the circumstances upon themselves.

He offers an example of a neighborhood that had kicked out a public health clinic for promoting contraception. Later the community suffered from the lack of overall health services. The situation gradually deteriorated but, over time, it had been forgotten that the community asked the government to remove the clinic in the first place.

In cases such as these, Alinsky makes clear that power must be personified through someone who organizers hold up as the responsible individual. He argues that it ultimately doesn’t matter whether the target is truly responsible or can change everything; organizers must generate publicity to make the individual appear as the key obstacle in front of progress.

Alinsky was known for very controversial and abrasive tactics, but they did work and they also revealed interesting insights into power relations. One key tactic he used was to “pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.”

In other words, he would pick a key politician or business leader and demonize them as the source of every problem. He’s tactics were known for being creative, crude, and sometimes hilarious political resistance actions that slowed private or government business. Alinsky noted on several occasions that the true key to success was to make a mockery of people who valued their position and prestige.

While isolating these figures, he noticed that the individual’s competitors would swoop in to take advantage of any power gaps. Business competitors, for example, would take advantage of a boycott on a competitor and political adversaries would exploit heavy criticism of their opponents. He concluded that the Haves are locked in a perpetual battle for power among themselves. These battles can come to an equilibrium unless disrupted from outside sources like grassroots movements.

The organizer could force quick concessions by isolating and undermining the figure’s economic and/or social capital. Because the target had so much to lose by being “taken out of the game” they would quickly give in to demands. For businesses and local governments, this often started a chain reaction; municipalities and industries would then need to adopt the same set of standards as the original target or they would be threatened with similar (but, crucially, not the exact same) treatment.

At this point, it’s natural to raise questions of whether the ends justify the means. Is it right to demonize one particular individual for a set of issues that they may not have created? And, what if the organizer knows that the target may not be the one responsible?

Alinsky emphasized that there is never truly a question of whether the ends justify the means. The only question that matters is – what means are available to achieve the ends? Alinsky gives no room for moral judgments, it simply boils down to what is within reach for organizers.

Famously, he asserts that the nonviolence of Mahatma Gandhi was not so much a moral endeavor as it was the only path available to disrupt the status quo at the time. Alinsky (and others) take it even further to suggest that Gandhi may have used violence had it been available to him. As evidence, Alinsky cites a passage of the Indian Declaration of Independence initiated by Gandhi in 1930. It reads,

Spiritually, compulsory disarmament has made us unmanly, and the presence of an alien army occupation, employed with deadly effect to crush in us the spirit of resistance, has made us think we cannot look after ourselves or put up a defense against foreign aggression or even defend our homes and families…?

These words offer indications that Gandhi may have been more open to the idea of violence than most realize – especially during the earlier years of the struggle. However, as in the above statement, Gandhi and other prominent figures lamented the broken spirit of Indians, suggesting that a violent insurrection was simply not possible to organize at the time. Nonviolence, argues Alinsky, was not a moral choice but the only tool available to Gandhi.

Regardless of whether or not one agrees with this theory, the point for Alinsky seemed to be that organizers do not have the luxury of deciding what means are just – it’s only a matter of finding what means are available and using them. This, of course, opens up room for debate that organizers should consider carefully before taking action.

Community Organizing in Practice: “Very Romantic Until You Do It”

While notions of fighting the power and organizing the resistance can sound inspiring, make no mistake about it – community organizing can be a brutal affair.

Organizers typically face enormous uphill battles in every direction when they begin. Local communities can be fractured, suffer from low morale or feelings of powerlessness, and have little agreement on potential solutions or even what the real problem is. The power to change things may seem to reside in distant places with untouchable people and through indecipherable processes.

Making things worse, in these circumstances, people are not always welcoming to organizers. Alinksy notes that more often than not people resent the organizer for breaking down psychological barriers which had prevented them from taking action on their own. He contends that there is a subconscious feeling of being looked down upon by an organizer.

To counter this, Alinksy stressed the need to build individual relationships with as many people as possible. He urged organizers to maintain a sense of curiosity for people’s interest and what makes them tick. By learning people’s motivations, lifestyles, interests, skills, and potential contributions, organizers are better able to get people what they want and to help them find the best way to contribute.

He noted that the efforts by organizers to get to know people shouldn’t be – and need not be – manipulative. Instead, the organizer is only meant to help the discontent tap into their voice and the power of community. As people come together a democratic and often chaotic process naturally unfolds.

This process, for Alinsky, is meant to drive the crux of any movement – while the organizer stands by to offer individual encouragement, stoke the flames of collective action, facilitate dialogue, and be the public face of the movement.

Crucially, the idea of tapping into the individual’s voice and offering them ways to reclaim power is not just an important idea for local change, but potentially the scaffolding of democracy itself.

Unfortunately, one could argue that the struggle to start this process of community organizing has become more difficult with time. Alinsky offered solemn words on the subject,

In our modern urban civilization, multitudes of our people have been condemned to urban anonymity—to living the kind of life where many of them neither know nor care for their neighbors. This course of urban anonymity…is one of eroding destruction to the foundations of democracy. For although we profess that we are citizens of a democracy, and although we may vote once every four years, millions of our people feel deep down in their heart of hearts that there is no place for them—that they do not ‘count.’

This idea has been expanded upon since Alinsky wrote the above paragraph. Some social scientists have been arguing for decades that the urban anonymity Alinksy mentions has been growing steadily since the 1950s. For instance, Robert D. Putnam asserted in his 2000 acclaimed book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community that the U.S. has seen a big decline in civic participation since the 1950s because our lifestyles have become more isolated.

This point is contested, however, and it’s worth noting that civic engagement has grown on social media over the last few decades. People may have simply changed how they engage in civic affairs rather than how much they engage.

“The Way Ahead”

Being aware of the basic discussions above is a good start for organizers because they will inevitably encounter many of these notions in their work. Organizers will face a series of events that involve everything from relationship building, political negotiation, confrontation, strategic planning, and more. Thinking about these scenarios ahead of time, then, can give organizers a major advantage.

There is much more to learn, of course. Especially, about “how the rubber meets the road” in community organizing. If you would like to learn more, we suggest the following resources:

- The principle book highlighted in this post: Rules for Radicals

- These Street Civics posts: