Understanding of the U.S. government begins by looking at the three branches of government.

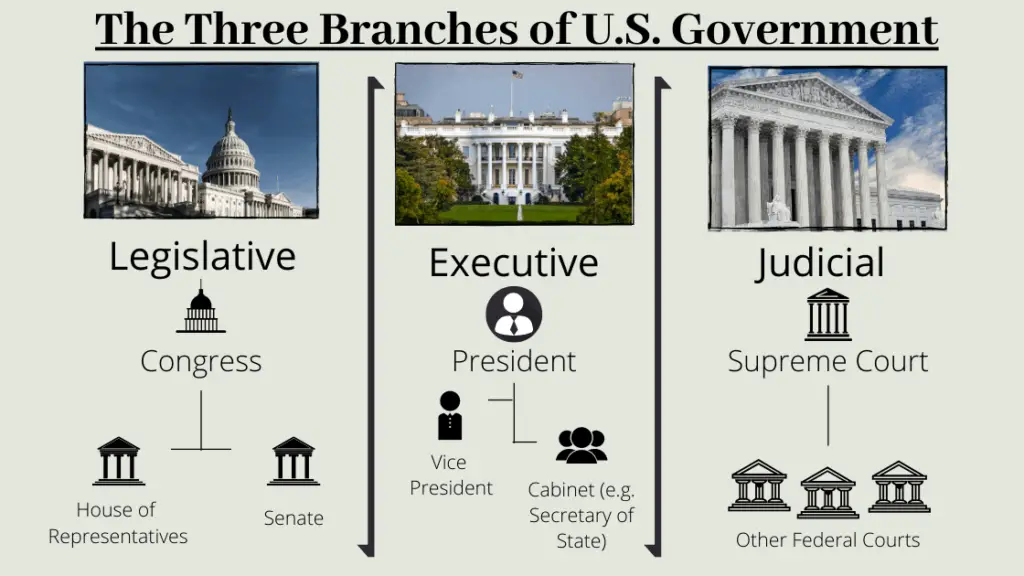

The U.S. government is made up of three branches: the legislative branch (Congress), which makes laws; the executive branch (the president & administration), which implements laws; and the judicial branch (the Supreme Court and federal court system), which interprets laws.

The branches of government are originally laid out in the Constitution. Writers of the Constitution (often called “Founding Fathers”) designed the U.S. government so that each branch had limited power (referred to as the ‘separation of powers’). This design was an explicit attempt to limit the political power of any one individual or group of individuals. The design was a response to the monarchy of the British Empire.

The three branches of government and how they relate to each other have changed over time. So, in this post, we’ll look at the original design of the three branches and what has changed since the original founding of the government.

The Three Branches of the U.S. Government on Paper

The following section describes the branches of government ‘on paper’ or as laid out in the U.S. Constitution and other foundational legal documents.

Key Responsibilities of Each Branch in the U.S. Government

| Legislative Branch | Executive Branch | Judicial Branch |

|---|---|---|

| Makes laws | Carries out laws | Interprets laws |

| Has ‘power of the purse’; controls taxing and spending policies | Controls military | Decides if laws or presidential actions are unconstitutional |

| Can declare war and the Senate must ratify peace treaties | Controls foreign policy and diplomacy | |

| Regulates interstate and foreign commerce | Can issue executive orders, presidential memoranda, and proclamations | |

| Senate confirms presidential nominations for public officials | Nominates public officials (includes Supreme Court justices) |

The Relationship between the Branches: 3 Examples of Checks and Balances

The relationship between the three branches of the U.S. government is often described as a series of ‘checks and balances’ in which the three branches regulate one another. In this way, each branch of government has limited power and there is continuous scrutiny of each branch’s behavior.

Here are three key examples of how the branches regulate one another.

- Congress makes laws, but the president can veto laws (or stop them from being enacted). In turn, Congress can overrule the President’s veto with a two-thirds majority vote in each chamber. This makes the process of creating law a back-and-forth between the legislative and the executive branches.

- The president commands the military, but only Congress can declare war. The Senate must also ratify peace treaties. In this way, both branches are needed to decide when the country goes to war and the conditions for peace.

- The judicial branch decides whether or not Congress and the president are following the law (a process called ‘judicial review’). In turn, the president appoints the judges who sit on those courts and the Senate confirms those positions. All three branches are involved, then, to make sure no branch ‘gets the final say.’

Legislative Branch (Congress)

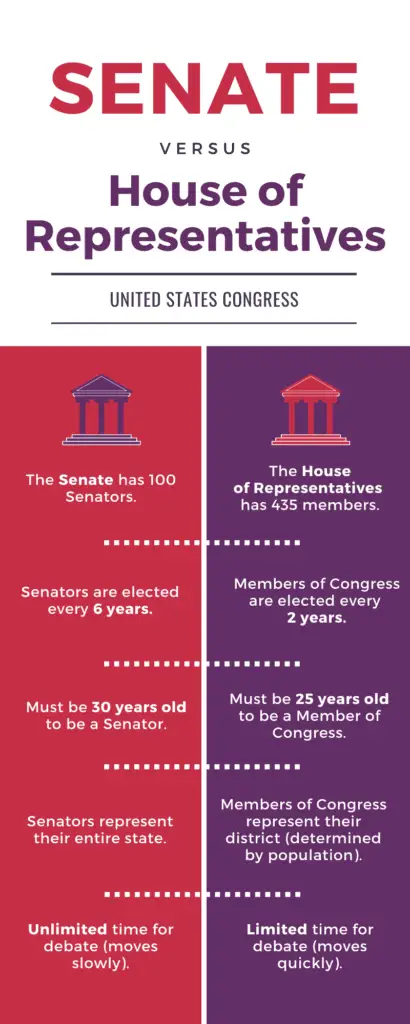

Congress is the legislative branch of the U.S. government; that is, it has the power to make laws. The branch is further divided into the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Each member of congress is elected directly by the people of their state or district. Each state is allowed to send two Senators. The number of representatives each state sends to the House, on the other hand, is determined by the state’s population. The infographic below shows some key differences between each chamber.

Making New Laws

To make a new law, both the Senate and the House must approve of the same proposal by majority vote. A draft of this language is called a ‘bill’ and can be introduced in one or both chambers. There are some exceptions, for example, tax bills must originate from the House.

If a bill is passed by both the Senate and House, it goes to the president. The president can sign the bill which makes it law or the president can ‘veto’ the law by sending it back to Congress. If the President vetos the bill, Congress can overrule him with a vote; a two-thirds majority is needed in each chamber to override a veto.

If the president does not sign the bill, it automatically becomes law in ten days. However, if Congress is not in session at the end of those ten days, the bill does not become law (called a ‘pocket veto’).

Executive Branch (President)

The executive branch is directed by the president. The president’s primary responsibilities are to serve as a head of state for foreign affairs, command the military, and carry out the laws set out by Congress.

The president, however, is not elected directly by the people like Members of Congress. Instead, the president is chosen by the ‘electoral college.’ The electoral college is a process (not a place) by which the people of the U.S. elect representatives (known as ‘electors’) who in turn cast a vote for the president.

In total, there are 538 electors who choose the president. A candidate needs 270 electoral votes to become president. If the election is a tie, the House of Representatives chooses the President and the Senate elects the Vice President (known as a ‘contingent election’).

Each state has the same number of electors as delegates in Congress; so two senators plus each representative in the House. The District of Columbia, the capital of the U.S., is also given three electors but is not a state.

The executive branch also includes the vice president and over 5,000,000 government workers that staff the many departments, agencies, councils, and other offices of the executive branch.

Often when people think of government ‘bureaucracy’ or ‘red tape,’ it’s the executive branch they are imagining. The infographic below manages to squeeze every office of the executive branch onto one organizational chart. Readers can get a sense of just how big the branch is!

Judicial Branch (Supreme Court)

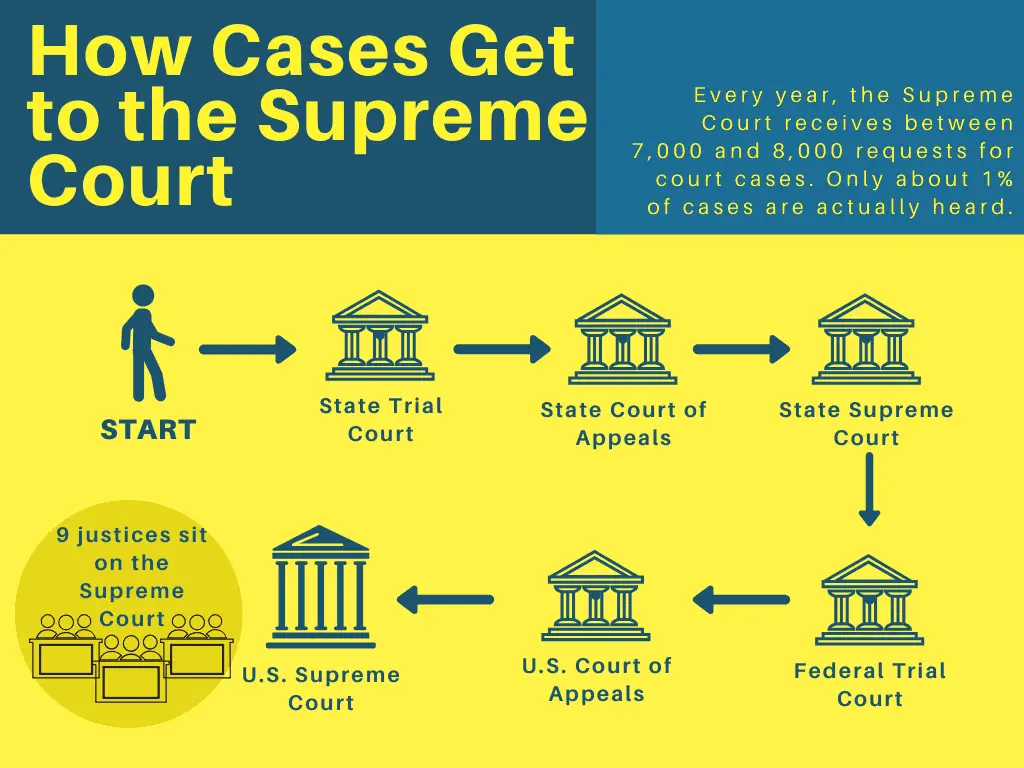

The judicial branch is the system of courts that decide how to interpret laws when disputes arise. The judicial branch also decides if laws made by Congress or actions carried out by the executive branch violate the Constitution. The courts are intended to be the non-political “umpires” of government.

The President appoints Supreme Court and federal judges and they are confirmed by the Senate (though some courts have special jurisdiction and are not confirmed by the Senate). Nine judges (or ‘justices’) sit on the Supreme Court with one serving as the ‘Chief Justice.’ All federal judges confirmed by the Senate serve until they retire, quit, die, or are removed by special procedures.

The highest court in the U.S. is the Supreme Court, which sits on top of a system of lower courts. Because of the high number of court cases in the U.S., very few (70 or 80) cases are heard by the Supreme Court each year. As a result, most cases are decided at lower levels.

The Three Branches of Government in Reality

The U.S. Constitution was written in 1787. It should be no surprise then that the institutions created by the documents have changed in the over 230 years since the document was published. In fact, the Constitution was left open-ended in a number of areas on purpose in order to allow the system to adjust to changing circumstances.

As our table above shows, the Constitution did not spell out the powers of the judicial branch or how it should be organized in as great as detail as the legislative and executive branches. The process of judicial review mentioned above, for instance, was not granted by the Constitution but was established in a landmark Supreme Court case in 1803 – Marbury v. Madison.

The Constitution also laid out a process for the document to be changed if legislators deemed necessary. Called a ‘living document’, the Constitution has evolved over the centuries through amendments. Amendments to the Constitution can have dramatic impacts such as the Thirteenth Amendment which freed the slaves.

In the modern era, however, trends have emerged that have put serious limitations on political representation and access. In 1929, Congress permanently capped the number of seats in the House of Representatives at 435. As the population of the U.S. continues to grow, more people are represented by the same amount of lawmakers.

In a 2018 Pew Research study of industrial democracies, the U.S. had the highest population-to-representative ratio among its peers by a significant margin. In the U.S., there are approximately 747,184 people for every representative in the legislative branch. (In a distant second place, Japan had 272,108 citizens for every lawmaker and Mexico had 247,965 people per legislator.)

Which Branch of Government Has the Most Power and Why?

A consensus is emerging that the president and executive branch have accumulated more roles and power than the legislative and judicial branches. In some cases, Congress gave up power to the executive. In other cases, the executive has taken on roles meant for other actors including the states.

For example, Congress has gradually reduced its own role in military affairs and foreign trade agreements. One manifestation of this is that it has become routine for Congress to approve of international deals on a “fast track” basis – a quick ‘yes’ or ‘no’ without further input.

In the realm of military actions, the Korean War marked the first time an executive took the nation to war without Congressional approval. This set the stage for the Vietnam War and many military actions to follow. In response, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution of 1973 in an attempt to limit the president’s use of military force.

The impact of the Act is contested, however. Notably, former Member of Congress and educator, Mikey Edwards, argues that the Act had the opposite impact and actually gave more military power to the executive.

The War Powers Act’s impact notwithstanding, an emerging consensus suggests that the executive branch has gained more power than may have been intended by the Founding Fathers.

Are Political Parties the New Center of Power?

While procedural powers may have accumulated in the executive branch, a convincing argument could be made for a shifting center of power away from the institutions themselves towards the political parties.

Many argue that the increasing partisan deadlock in the U.S. has permeated every branch of government – including the judicial branch (which is supposed to be the non-political branch). If true, separation of powers, then, become secondary to party ideology.

Interested in hearing more about the modern political landscape? Check out this article on the Impact of Social Media on Politics.

Interested in Tracking Congress? Check out our post on How to Track Legislation.