Community organizing theory is a broad topic that has several subgroupings and intersects with many academic fields. To understand the idea better, it’s useful to start with an overview of popular topics and then look at a fundamental (and timeless) understanding of the idea.

Community organizing theory examines many concepts including power-relations, human interests, relationship building, democracy, community development, negotiations, and more. These theories often intersect with fields such as political science, sociology, economics, and other behavioral sciences.

The array of topics within community organizing theory allows ample room for practitioners to diverge along any given line of inquiry. So, there are many takes on how to create social change – evidenced by the vast amount of literature on the subject.

Nonetheless, there is a noticeable spectrum (or maybe more accurately, a plane) between two distinct styles – sympathetic and confrontational approaches. This is not the only way in which organizers differentiate, of course, but it is one of the most basic and visible manifestations of an organizer’s underlying approach or principles.

Sympathetic approaches to community organizing focus on relationship building and seek to cultivate self-actualizing individuals. Organizers of this sort try to leverage each person’s unique skills and perspective by encouraging self-development and collaboration. Theorists often reason that this process of nurturing individual strengths (or “community assets”) and strong personal networks naturally develops stronger, more inclusive, and equitable communities.

Confrontational approaches focus on interests and power. These techniques try to align interests within the community and attempt to exploit the interests of those in power. Theorists of this sort often maintain that strong civil society networks are a necessary counterbalance to the power of the state. Ultimately then, the goal is to alter relations between the Haves and the Have Nots (the terms often used by confrontational theorists).

It’s easy to see the merit of both sides and the two approaches aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Most organizers will (and should) combine elements of both in practice and, often, the approaches blend into one another.

The comparison to the Taoist symbol of the yin and yang for the title of this post may intrigue scholars of Eastern philosophy but might seem like a hokey stretch to others. What many in the West don’t realize, however, is that the symbol of the yin and yang has roots in ancient literature like the Tao Te Ching, which focused on an individual’s relationship with their environment as well as a leader’s, or in this case an organizer’s, relationship with their community.

The dueling approaches to organizing are captured well in the symbol representing the philosophy – the yin and yang. For purposes of organizing, the yin (or feminine) represents the sympathetic approach, which nurtures individual creativity and communal support. The yang (or masculine) represents the confrontational approach which harnesses collective interests to assert power.

Today, the Tao Te Ching is often put in the category of theology or philosophy and mostly overlooked by modern-day organizers. However, the work did examine very fundamental principles of (what we call today) community organizing.

The book’s near-primordial conception of social change offers the perfect starting point to examine community organization theory. Below takes a look at what organizers can learn from the ancient philosophy. Lastly, we’ll look at how we can apply this philosophy in the modern context with examples of two key organizers – Jane Addams and Saul Alinsky, who each embodied one of the approaches.

The First Organizer?

Lao Tzu was an ancient Chinese philosopher who is often cited as the author of the Tao Te Ching. While historians dispute the history of the text and authorship, most agree that the text came together during the Warring States Period in China during the 6th century BCE. The period was marked by constant battle between territory as the central power (the Zhou Dynasty) declined and lost control over the empire.

Legend has it that Lao Tzu tried in earnest to spread the idea of a peaceful and collaborative approach to ruling. Ultimately, though, he gave up hope trying to convince the elites and he decided to leave society to live in the wilderness. As he passed through the final gate to the countryside a guard recognized him and wouldn’t let him leave until he recorded his philosophy.

Lao Tzu accepted the guard’s demand and wrote the Tao Te Ching to capture the core of his teachings. The book’s central principle is that individuals and leaders should not strive to control events or their subjects but should allow for a natural unfolding. This unfolding is referred to as the Tao (or the “Way”).

The crux of the philosophy is that leaders must find peace within themselves in order to help their community thrive. For Lao Tzu, the leader is meant to set an example for their followers and, by finding peace within themselves first, their followers will do the same creating a more harmonious society.

It’s important to note that the philosophy doesn’t necessarily argue for no rules at all (although, less is better according to Lao Tzu). The point is that leaders who are at peace with themselves and with their people will act in alignment with the nature of their environment; the community will then behave more peacefully. In other words, leaders will enact more just and sensible rules if they and their people self-actualize.

For organizers, the concept can be thought of as working with and through the true nature of humans and their environment rather than attempting to impose structure or coerce others.

The book also makes the case for a harmonious balance between individual and collective responsibility. Lao Tzu was clear that leaders should seek to serve their followers as opposed to rule them and that they should try not to interfere with an individual’s ability to express their true nature.

This core tenant of Lao Tzu’s is precisely what underpins community organizing theory today. Organizers attempt to foster inner resilience and community cohesion, not to speak on behalf of others or to impose an individual agenda.

In fact, the philosophy spells out why the term “community organizer” is preferred in modern times over something like “community leader”; “organizing” connotes an open-ended act of bringing together as opposed to “leadership” which could imply subjugation.

As Lao Tzu said,

“So when the Saints wish to rule the people, they must, by their words, put themselves below the people. When they desire to be placed in front of the people, they must put themself after the people.”

Tao Te Ching, Text 66, Translation by Charles Johnston (altered pronouns, plurality, and conjugation from “he/him/his” to “they/them/their”)

The Yin, Yang, and Modern Community Organizing

While specific mentions of the yin and yang in the Tao Te Ching vary from 0 to 1 depending on the translation, the text is laden with references to the balance between opposites. The yin and yang symbol naturally became associated with the text (and Taoism more generally) because it captures the philosophy so well.

Looking at the symbol, the yin is the dark side which represents the feminine, negative, passive, and still. The yang is the light side which represents the masculine, positive, assertive, and energized.

It’s important to note, however, that when speaking of the yin as representing the “negative” it should be understood more in the metaphysical sense as opposed to any kind of value judgment. The negative is meant to be understood as empty space and creative potential.

The philosophy of Taoism argues that these opposing forces are in constant motion which always comes to balance. For example, the night is yin and the day is yang. Life is yang, while death is yin. Winter is yin and is always followed by summer, which is yang.

So what does this have to do with modern organizing? It turns out that this ancient philosophy might shed some light on an old organizing paradigm. Over the last few centuries, there has been a clash and even, at times, outright debate over sympathetic vs confrontational approaches. However, this ancient symbol captures the need for a balanced approach and a different way of viewing the modern conversation around community organizing theory.

To illustrate this better, we can look at two organizers – Jane Addams and Saul Alinsky – who each embodied one approach and how their relationship might reveal where organizers can go wrong.

The Yin Approach – Jane Addams and Sympathetic Knowledge

Jane Addams was a 19th and 20th-century American settlement activist and community organizer. Her style of organizing gained her worldwide renown during her heyday. However, when Addams spoke out against the U.S. entering World War I, several of her critics attacked her with gender-based insults which severely damaged her reputation. As a result, her work and writings had been all but forgotten by community organizers and theorists until the 1990s when her writings were resurrected.

Addams embodied the sympathetic (or yin) approach remarkably well. Her work is far too prolific to do justice in a few paragraphs, but the cornerstone of her organizing was the Hull House – a housing complex set up by “university women” to assist working-class women and newly arrived immigrants. The house opened in Chicago in 1889 and became a Mecca for community support and creativity.

Addams and her associates set up the house primarily to help elevate women with little opportunity. They did so by performing duties neglected by the city such as performing childcare, looking after orphaned children, sheltering domestic abuse victims, acting as on-call doctors (many doctors would not visit those communities at the time), as well as offering a space for women to organize on the social issues of the day.

Addams was not just a “doer,” she was also a leading thinker and author. One of her most fundamental ideas was that of “sympathetic knowledge” which posits that knowing one another better increases social connection and the likelihood of emphatic and collaborative action. Her writings were one of the first modern appearances of this type of organizing and her works had a tremendous influence on the field – even when she, herself, had been forgotten by theorists.

Addams’ devotion to the sympathetic style of organizing created space (or yin) for women and some men to flourish. Many of those who participated in activities or lived at the Hull House used their experience to advance ideas in fields as diverse as economics, higher education, business, and the arts. Her work was even the basis for the founding of an entirely new field of research at the time – sociology.

In truth, though, Addams is really an example of a balanced approach to organizing. While her theories on sympathetic knowledge were important contributions, they did not entirely define her work. Addams was able to confront policymakers and community leaders when need be. However, she was not antagonistic and her confrontations may have looked more like tense negotiations rather than hostile or antagonistic acts of political resistance.

Note that Addams also embodied Lao Tzu’s principle of “leading from behind.” Addams had written extensively on the struggle to remain humble in her work and to ensure that she was putting the voices of impacted communities first. This aspect of organizing almost seemed to torment her at times – something Lao Tzu might have seen as a sign of genuine leadership.

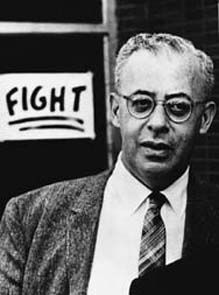

The Yang Approach – Saul Alinsky, the “Freud of Community Organizing”

Saul Alinsky is likely one of the most famous figures in organizing theory and is sometimes referred to as the “Freud of Community Organizing.” He, like Addams, was both an activist and theorist. Alinsky, again like Addams, made a name for himself by organizing immigrant communities in Chicago. Unlike Addams, however, he became particularly known for his unorthodox, confrontational, and often antagonistic tactics of pressuring lawmakers.

Alinksy is the quintessential confrontational (or yang) organizer. He was primarily interested in how to align interests within the community (for example, between African American and Italian immigrants) and how to leverage collective action against those in power. While Alinsky was a far-left activist, his most famous book Rules for Radicals has influenced countless movements across the political spectrum ranging from Occupy Wall Street to the Tea Party movement.

For Alinsky, the primary aim of organizing was about how the Have Nots could take power away (or back) from the Haves. With this underlying principle, Alinsky concluded that the means with which organizers used to achieve the balance of power was incidental; he was not concerned with the morality of certain means and even chided the very question of morality as it relates to organizing. Alinsky contented that a true organizer uses what’s available and that’s that.

This philosophy led Alinsky to some pretty outrageous tactics to pressure those in power. For instance, he once worked with an African-American community that was trying to get concessions from the white upper-class majority. In this particular community, the white elites treasured the town’s theatre. So, Alinsky proposed to the African American activists that they all purchase tickets to a show. Before arriving, they would each eat a can of beans and let their flatulence loose during the performance.

The idea was to make a mockery of what the Haves treasured and that is often where Alinsky went from being confrontational to antagonistic. He consistently remarked that to truly induce change from the Haves, organizers needed to embarrass and humiliate them in unexpected ways to threaten what they valued.

Alinsky was able to get important concessions to underserved communities throughout his career, however, he also became known as a pariah due to his tactics. In some ways, Alinsky’s reputation and career represent what happens when an organizer refuses to balance their tactics.

When there’s too much yang and not enough yin, organizers may be cast aside as radical nuisances. Conversely, if there’s too much yin and not enough yang, organizers may build strong communities but fail to bring about institutional change. This imbalance or rigidity of approach, according to the Tao Te Ching, is tantamount to death and, for organizers, an unbalanced approach sets unnecessary limitations on a movement.

Interestingly enough there was some overlap in the lives and works of Alinsky and Addams. Alinsky was on the record as denigrating Addams’ sympathetic approach, which again shows the lack of balance in his work. However, more recent examinations of the relationship show that Alinsky was more of a protege of Addams than he was a rival; a funny but unsurprising note considering the Tao Te Ching stresses that the yang is born from the yin.

It’s worth pointing out, however, that even Alinksy would have agreed with Lao Tzu that true leaders are meant to serve. Alinksy repeatedly emphasized in his work that organizers were meant to help the community speak for themselves; they were not there to speak on anyone’s behalf or push a particular agenda. Even Alinsky, a hostile organizer, grasped this point well, which is likely one reason why he was so successful despite being disliked by many across the political spectrum.

Final Words – Balance for Organizers

By looking at two big camps of community organizing theory alongside one of the most ancient pieces of “community organizing” literature, we can see that effective organizing is born from at least two things:

- An organizer’s willingness to put the community first and to “lead from behind.”

- A balanced approach that uses both sympathetic and confrontational methods.

To be sure, there is much more to explore on the subject of community organizing theory, but these two basic understandings coupled with the examples provide a solid entre into the topic. For more on this and related subjects, check out these posts: