Advocacy can often sound abstract, but the process is more concrete than you might imagine. Like any other profession, advocacy has some set practices and even supportive industries that have grown around it such as government tracking software. (But, don’t let that intimidate you – anyone can be an advocate!)

Advocacy means to advance social causes and/or policy recommendations through public education, grassroots organizing, and lobbying. Ultimately, advocates seek social and/or institutional change by moving public opinion and persuading policymakers.

The day to day activities of advocates can vary greatly, but usually include some of the following:

- Developing communication materials (such as flyers, reports, or opinion articles),

- Event organizing,

- Lobbying policymakers,

- Media relations,

- Meetings with experts, academics, bureaucrats, and other advocates,

- Organizing or attending coalition events (groups of like-minded organizations and individuals),

- Public speaking engagements,

- Research and analysis,

- Social media messaging,

- Spending time with impacted communities, and

- Strategizing and planning.

There’s much more to being an advocate, though, and it can be really exciting work. Below is a quick introduction into the world of advocacy, and you’ll find answers to the following questions:

How Do You Start Advocacy?

It can be difficult to know where to begin when trying to advocate for a cause or recommendation. So, here’s a quick outline to get you started.

Start advocating by:

- Researching the issue.

- Analyzing political power and risks.

- Building professional relationships in the issue area.

- Learning relevant political and government processes.

- Developing an “ask” (or policy proposal).

- Meeting with officials and policymakers.

The key in the beginning stages of advocacy is to be absorbing as much as possible about the political environment, the relevant policy-making processes, and the network of actors that are involved in the issue area.

After an initial “intel gathering” stage (which can last months), the more proactive stages of advocacy can begin. Though, you’ll want to analyze which actors have power and how you may be able to reach them before approaching policymakers, the media, and the public.

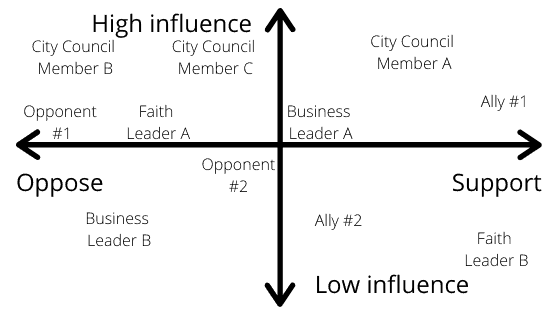

Power mapping is an old practice that helps analyze power around an issue; it makes use of a simple graph like the one below.

You can plot the actors relevant to the issue area to look for connections and leverage over decision-makers. Here’s an example of what a generic local issue might look like:

In the above example, advocates may want to look for connections to City Council Member C – possibly through Business Leader A, though any connection helps! If you’ve found a leader with high influence and need to zero in on persuading that individual, you can take the analysis one step further by analyzing the relationships to that individual. Here’s an excellent example:

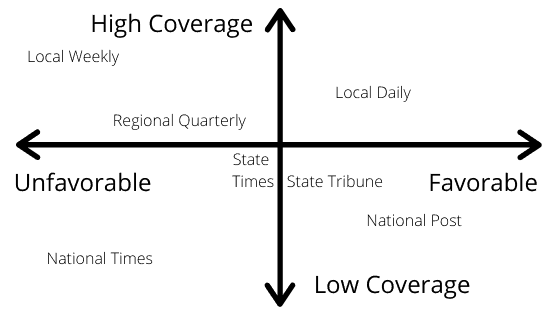

Pro-tip: it’s a good idea to have a separate media map, which looks at the media coverage of the issue. Here’s an example.

In the above example, the advocate would likely aim to interact with the Local Daily, at first, and aim to increase favorable coverage in the State Tribune and, hopefully, the State Times later on. Local advocates should never discount national press if the issue is serious enough.

Depending on the issue though, it could take a long time before the national media find it newsworthy and it may only be covered briefly without any follow up. So, advocates want to aim for the media outlets that will have sustained coverage and can influence public opinion and policymakers over the long term.

With the above graphs, advocates can begin designing appropriate “asks” or proposals. Ideally, the asks will:

- Coalesce support from allies and supporters,

- Increase media coverage,

- Convert opponents, and

- Move the issue forward.

While beginning with a large ask may be necessary if the issue is urgent or the ask is clear enough, advocates sometimes start with small asks to socialize the issue among the public, policymakers, and the media. In practice, advocates will likely find they have an overarching ask that they build towards through small reforms and changes to public opinion.

For example, the women’s suffrage movement asked for a constitutional amendment from the beginning. Changing the most fundamental legal document of a country is the biggest “ask” there is in the advocacy business. The movement, though, consisted of countless acts to build public support and create little policy changes that eventually added up. It took almost 100 years of relentless effort before the 19th amendment was finally added to the U.S. constitution.

How Do You Advocate?

Once you have a good handle on the issue, the power structures at play, and a good ask, you’ll want to start taking action to advance your issue.

To advocate, develop talking points as a guide for messages to policymakers and the public. Then, create and distribute materials such as flyers, infographics, brochures, opinion articles, reports, etc. From there, present your materials and proposal to policymakers, the media, and issue experts.

The process is more complex in the real world, of course. Creating a substantial change can require grassroots strategies in later stages. But, for new campaigns, starting small with something like a series of infographics is a great way to practice messaging techniques and, at the same time, begin building a catalog of materials quickly.

At this stage, it’s a good idea to introduce yourself and your ask to policymakers and their staff. Ideally, you’ll want to build long term relationships with these people, so it’s best to be non-combative (but firm) in these meetings. If you’re new to meeting with officials, check out our post that outlines how to lobby for more.

Introductory meetings are best when you can bring a group of like-minded advocates and constituents together to meet with a policymaker. While it helps to have big numbers in these meetings to show support for an issue, going as an individual is better than not going at all. A single meeting, though, may not be enough to move a policymaker; a campaign may be needed to sustain pressure on decision-makers.

What Is An Advocacy Campaign?

What type of advocacy work exactly constitutes a campaign is a little subjective. In general, though, you can think of it as the following;

An advocacy campaign is a series of public education and lobbying actions intended to change attitudes and/or policies, often through escalating tactics that increase visibility and pressure on officials. A campaign may be carried out by a single entity or by many independent actors that coordinate.

Some advocates and organizations may be entirely dedicated to a single campaign. Others may operate multiple campaigns at the same time, which may or may not be related to one another.

For example, an organization concerned with clean water may run a campaign to improve protections for a nearby lake while at the same time carrying out a campaign to improve clean drinking water at the state or national level. In this way, organizations can work toward overarching goals by focusing on specific policies that help move an overall issue forward.

There is no set way to go about building a campaign, but advocates will want to consider the following actions to get started:

- Build an identity for the campaign with branded materials, slogans, etc.

- Build a coalition (or a group of organizations and/or individuals that will commit to the campaign and coordinate either formally or informally).

- Define a strategy and plan a series of actions that start small and build toward more visibility and pressure on policymakers.

- Create supporting documents such as flyers, brochures, reports, analysis, opinion pieces, and other communication materials.

A widely known example of a successful campaign is the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). The movement is often considered one of the best-executed campaigns of all time and the coalition even received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 – just five years after being founded!

The campaign was led by the famous activist Jody Williams who helped coordinate a coalition of over 1,000 organizations in over 60 countries to advocate for the abolishment of landmines. The campaign caught fire in the mid-90s and it eventually led to the international treaty called the Mine Ban Treaty (or Ottawa Convention). 120 countries signed the treaty – drastically reducing landmine use around the world.

While the ICBL was an impressive global effort, advocates should not be intimidated. Some campaigns never reach the international level or even national level and are still successful. Even if you’re beginning with one person, a campaign can snowball over time and suddenly find an outpouring of support.

If you’re looking to begin a campaign, you’ll need to know how to set up digital communications operations. Street Civics breaks down how to get started with digital campaigns here.

You’ll also want to be familiar with some fundamental strategies for grassroots organizing. You can find seven of the most basic strategies outlined here.

Recent Posts

Writing a letter to the president can be an effective way for advocates to have their voices heard, influence policy decisions, and move public opinion if done with some planning and intentionality....

This is a straightforward guide for organizers who are planning protests. The below sections layout the logistics of organizing a demonstration, strategies, and tactics, and how to leverage the event...