This is a straightforward guide for organizers who are planning protests. The below sections layout the logistics of organizing a demonstration, strategies, tactics, and how to leverage the event for political change.

Organizers and interested readers may also want to read the companion piece to this article – A Protester’s Guide to Effective Action, which outlines the roles of individuals within protests. In that article, we address important issues such as how individuals can come prepared and what to expect from law enforcement; information that is essential for organizers to understand before preparing a protest (if there’s time to prepare that is). This post covers the subjects outlined below.

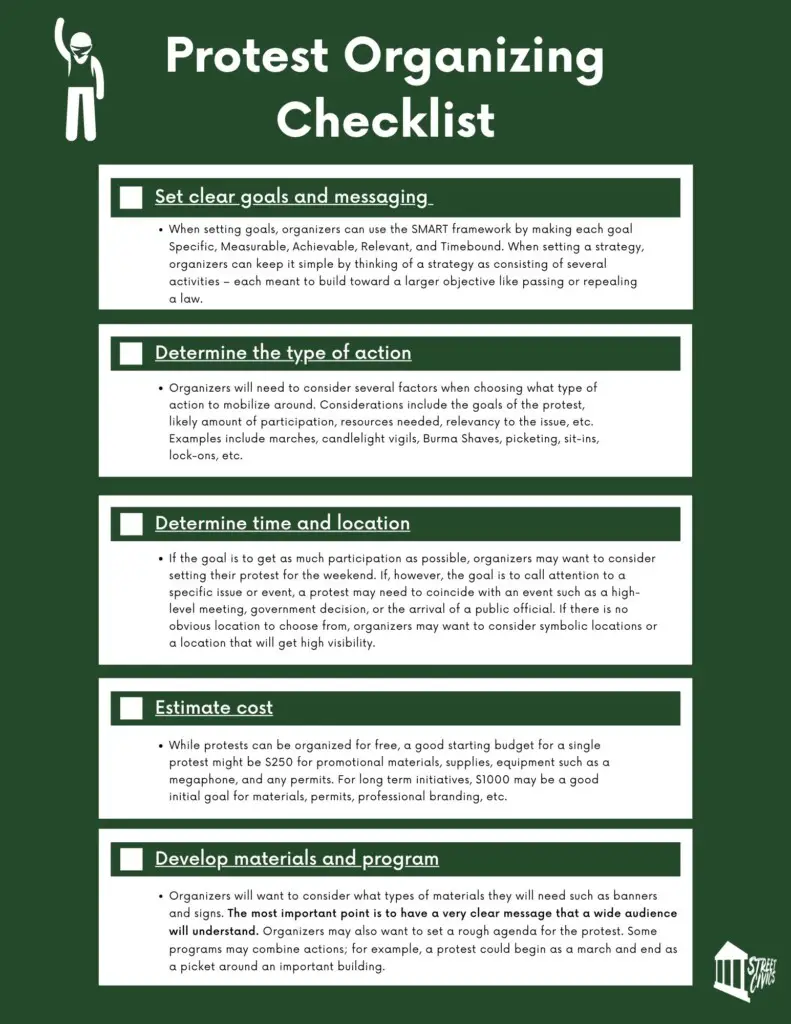

Protest Organizing Checklist

Setting Goals and Strategy

Determining Type of Action

Determining Time and Location

Estimating Cost

Developing Materials & Program

Organizing Support Roles

Determining if Permits are Required

Understanding Civil Disobedience

Advertising the Protest

Most Effective Protest Methods

Turning Protests into Political Change

How to Organize a Protest

Activists should keep in mind at least nine steps when organizing a protest.

- Set goals and strategy

- Determine the type of action

- Determine time and location

- Estimate cost

- Develop materials and program

- Organize support roles

- Determine if permits are required

- Understand civil disobedience

- Advertise the protest

Below is a downloadable organizing checklist and the following sections go into more detail on each step.

Protest Organizing Checklist

Setting Goals and Strategy

When setting goals, organizers can use the SMART framework by making each goal Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timebound.

When setting a strategy, organizers can keep it simple by thinking of a strategy as consisting of several activities – each meant to build toward a larger objective like passing or repealing a law.

Below is an example of a set of objectives for a single (small) protest, followed by a set of objectives that represents a larger campaign strategy. The below examples assume the strategy will have multiple protests but, of course, that might not always be the case.

Activists will also note that not all example goals below are advisable in all circumstances. For example, organizers should carefully consider the pros and cons of collecting identifying information from participants for things like email lists, which could be used by law enforcement or the opposition for surveillance, arrests, and/or harassment.

Activists should regularly review their goals and update them according to the changing situation. However, organizers will also want to remain flexible and use the goals and strategy as a helpful, but rough roadmap for change.

Example Goals for Protest

| Goal | Who is responsible for measuring and how will they measure it? | Timeline |

| At least 150 participants attend the rally. | Activist A will collect signatures and keep count of participants as they enter the area. | By end of protest. |

| One or more media outlets cover the event. | Activist B will monitor media during and after the protest. | Within one week of the protest. |

| At least 25 new supporters sign up for the email list. | Activists C will collect signatures for the supporter list. | By end of protest. |

| At least 25 new supporters sign the petition. | Activist C will collect signatures for the petition. | By end of protest. |

| At least 15 participants call their council member. | Activist D will monitor a phone bank and hand out flyers with instructions on how to call council members. | By end of protest. |

| At least 15 participants are given a small group training on the situation and their rights. | Activist E will conduct small group trainings for participants. | By end of protest. |

Example Campaign to Overturn City Council Resolution 123

| Activities | Goal | Resources needed | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protests | Reach an average of 125 participants each week until the resolution is overturned. | Five organizers to be present at each protest; one organizer to advertise and handle social media in between protests; Approximately $250 for initial printing, banners, and misc. Supplies. $50-100 each following week for additional printing and resources. | Every Wednesday until the resolution is overturned. |

| Media engagement | Generate media attention each week with at least one piece of coverage. | One organizer to liaise with media and provide press releases and/or coordinate article writing campaigns. | Ongoing until the resolution is overturned. |

| Build a list of supporters | Collect over 300 emails of supporters. | One organizer to maintain the list and collect signatures. | By the end of the second protest. |

| Present petition to council members | Collect over 500 signatures for a petition and publicly present it to the city council. | One organizer to maintain the list and collect signatures. | Present the petition during the upcoming town hall meeting. |

| Call-in campaign | At least 75 participants call their council member. | One organizer to train and provide instructions to supporters on how to call council members. $25 for instructional hand-outs. | Before the town hall meeting. |

| Community empowerment | At least 75 community members are trained on the situation and their rights. | One organizer to train community members. $75 for instructional hand-outs. | Before the town hall meeting. |

Determining Type of Action

Organizers will need to consider several factors when choosing what type of action to mobilize around. Considerations include the goals of the protest, likely amount of participation, resources needed, relevancy to the issue, etc.

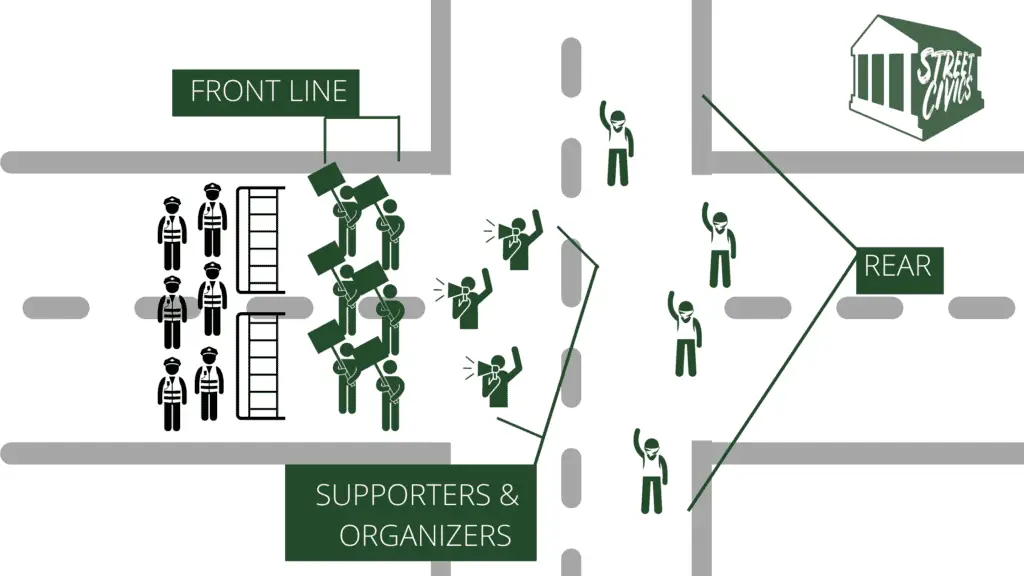

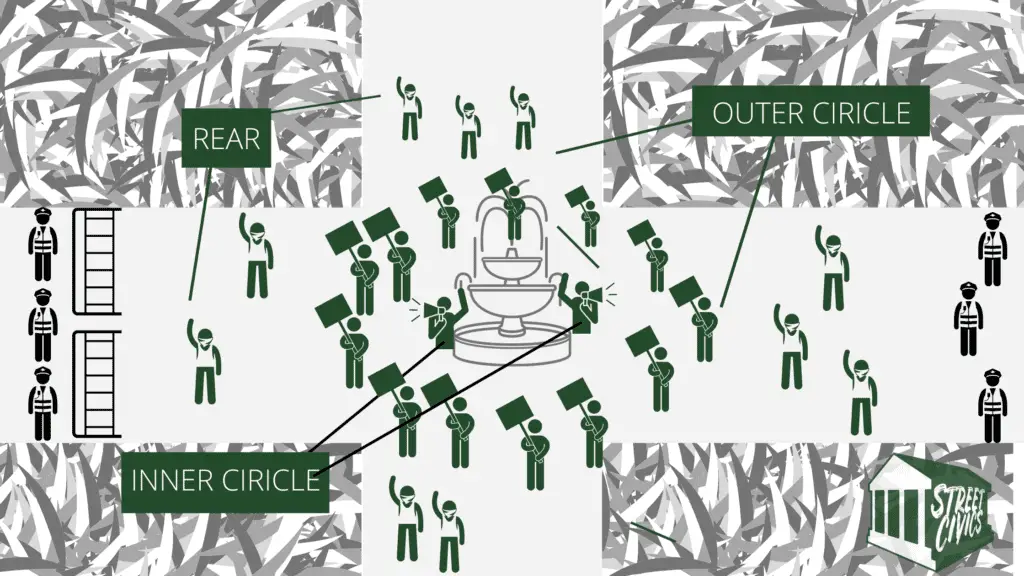

Note that large groups of people always present safety concerns; it may be a good idea to keep organizers dispersed throughout the crowd to provide demonstrators with direction as well as to be ready to act as a calm facilitator in the event of an incident.

Organizers should be ready to remind the crowd to ‘WALK, DON’T RUN’ if panic arises; saying this calmly and assertively can help prevent trampling. Those who yell, however, should be mindful if pepper spray and/or tear gas have been fired as they will not want to inhale deeply around those gases. Organizers should try to yell the phrase loudly before the gases disperse and then they should cover their nose and mouth.

Depending on the density of the crowd, organizers may also want to keep an eye on accessibility both for entering and exiting participants. Controlling the flow and/or creating space may be necessary to prevent issues of overcrowding, if participants need to evacuate, or if medical personnel need to enter the crowd.

Types of Protest Actions

| Action | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rallies and speeches | Rallies and speeches are typically organized demonstrations with a loose agenda and set speakers. | This tactic puts the organizers at the center. While effective with the right personalities, it can also drown out other voices if organizers aren’t mindful. (For megaphones or audio equipment see this Street Civics resource.) |

| Marches | Marches are organized processions of demonstrators that often start at a convenient rally location and then parade activists slowly toward a strategic or symbolic location. | Marches are a good way for protesters to cover more ground and reach a larger audience by moving through town; this strategy can help both with building public support and by encouraging participation from bystanders. These types of protest can often provide dramatic imagery for the media as well. |

| Chanting & holding space | Chanting is usually a default for groups that have gathered together spontaneously, in response to an event, or if protests have carried on for prolonged periods of time. | Random chants and generally holding space are part of any demonstration, but are not necessarily enough to distinguish a movement. If protests are prolonged, organizers may want to consider introducing distinct demonstrations of solidarity like unique gestures, singing or lighting candles to help build an identity for the movement. |

| Candles and vigils | Vigils are public ceremonies that invite supporters to light a candle at a specified time and/or place. | This tactic can start spontaneously, but requires organizing for larger crowds. Often, candles and sources of fire need to be passed out or around. More space than usual is needed to give people room (they may need to sit down), but the more space that’s used the bigger impression it makes. |

| Singing and celebrations | Singing and celebrations can be a form of protest in the right context. The optimistic attitude of this tactic may help gain public sympathy and support. | These tactics appear on some scale at many demonstrations. However, they can also become a distinct feature of a movement in certain circumstances. Celebrations may have one of the lowest participation barriers and could help attract mass participation. |

| Cacerolazo (or casserole) | A Cacerolazo or casserole is a demonstration where protesters bang on pots and pans or other items to make noise and call attention to an issue. | These tactics have been used in the West since the 1830s. The tactic has a low participation barrier as most people have something they can bring to make noise with. This tactic can be a memorable and defining feature for a movement and may help grab media attention. |

| Burma Shave | Burma Shaves put demonstrators along roadsides or thoroughfares with signage and public message tools. (The term comes from an old shaving cream company that was famous for using roadside signs as an advertising device.) | Burma Shaves are great options to cover more ground with less demonstrators. Organizers who have low participation, might consider splitting protesters into small teams around town to cover more ground. Clever signage and messaging is crucial for this technique. |

| Human Chains | Human chains have participants link arms and from a line which can either form a barrier or simply link people across places (sometimes across cities or even countries) in a show of unity. | Human chains are well-known but still underutilized tactics of protests. The more space activists can link the more it moves the general public and policymakers. |

| Street and Guerilla Theater | Theater can be a powerful way for activists to make a point with devices like satire. Street theater is often organized in advance, while guerilla theater can be surprise performances in unlikely places. | Theater can be an effective tool for organizers. However, in order to carry out theater well, organizers should consult and work with local artists and actors. |

| Blocking traffic and disruptions | Blocking traffic on major roads, peacefully stopping economic flows and/or disrupting daily life for the community are tactics sometimes used by protesters. | These tactics can call attention to an issue quickly but can also alienate potential supporters who are inconvenienced by the disruption. This tactic is directly confrontational and some rogue participants may destroy property, which can decrease a movement’s chance of success. Organizers should also be aware of any relevant local laws. |

| Banner dropping and public messages | Activists sometimes organize a banner drop or an unveiling of a message in a public space. | These tactics can be effective ways to get messages across. Beware that authorities often respond by trying to take down the message which can result in altercations. This tactic takes a bit of planning to do well. |

| Picketing | Picketing assembles activists outside a strategic location and/or outside an event, usually with the hope of dissuading others from attending the event or going inside. | Picketing is a tried and true tactic of trade unions, however, it’s a versatile tactic that can be relatively effective even with low numbers. |

| Lock-on | Lock-ons are when protesters secure themselves to a stationary object in order to make it difficult for them to be removed by authorities. | These tactics can require some real sacrifice and put protesters in very vulnerable positions. Demonstrators using these tactics should have a clear plan and should think carefully about how they will meet their basic needs, go to the bathroom, etc. |

| Sit-in | Sit-ins are tactics where protesters occupy a space and refuse to leave. | These tactics are effective and were employed with successful results during the civil rights movement. They are also less risky than some tactics like Lock-ons and have a lower participation barrier. |

| Die-in or lie-in | Die-ins or lie-ins are when presters pretend to be dead as a group in a public space to raise awareness for an issue. | These tactics also have a low participation barrier and can be part of a larger protest scene. They can be effective visuals. |

| Love-in | Love-ins are peaceful demonstrations centered on meditation, love, music, and even sex or drugs. | These tactics were popular in the 1960s with hippie counterculture. They offer low participation barriers, but organizers should keep in mind that the more relatable the scene is, the more likely they will gain public support. |

Determining Time and Location

If the goal is to get as much participation as possible, organizers may want to consider setting their protest for the weekend. If, however, the goal is to call attention to a specific issue or event, a protest may need to coincide with an event such as a high-level meeting, government decision, or the arrival of a public official.

If there is no obvious location to choose from, organizers may want to consider the following typical arrangements:

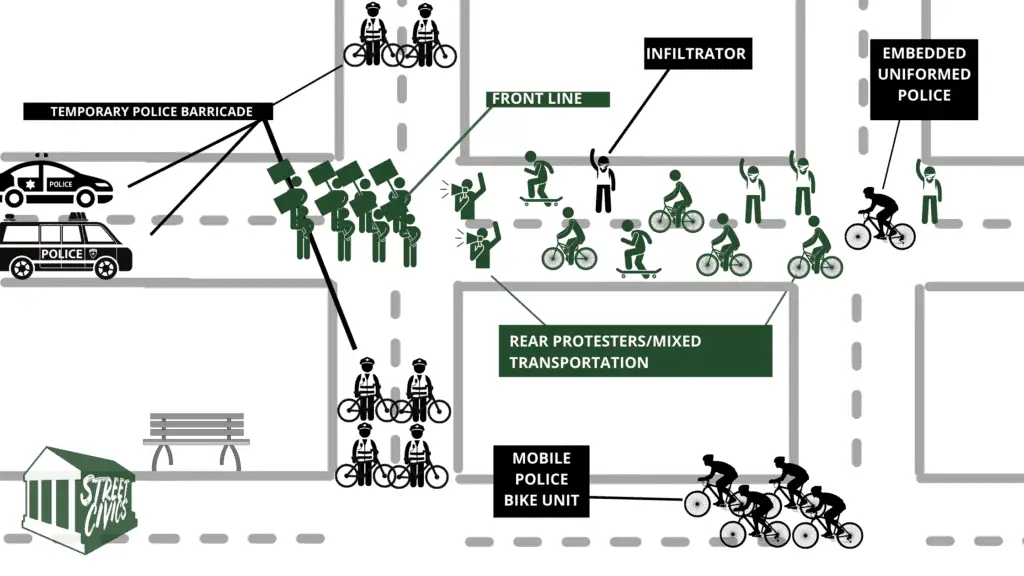

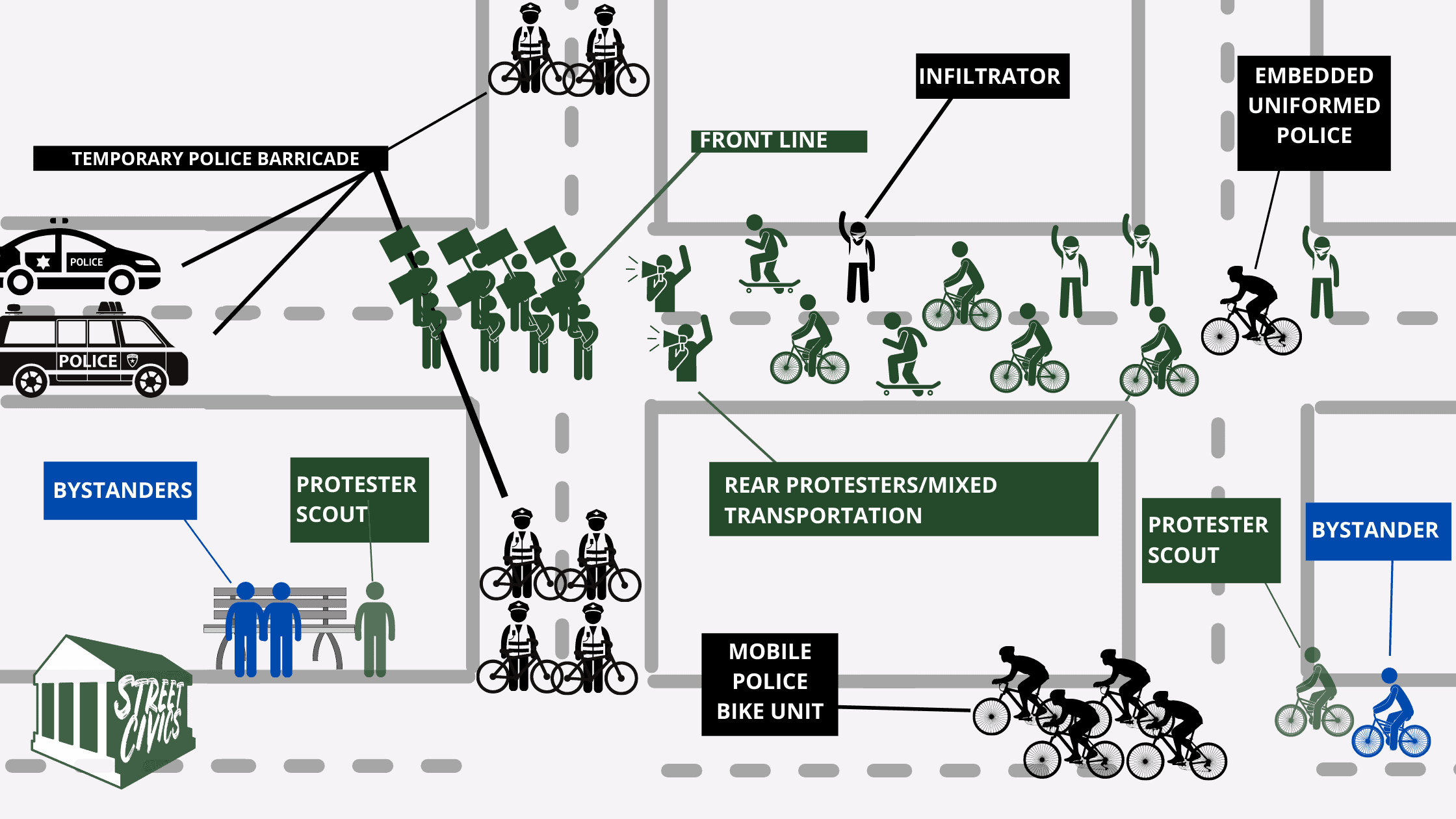

“Front Line” Protests

“Speaker Circle” Protests

Marches

Estimating Cost

While protests can be organized for free, a good starting budget for a single protest might be $250 for promotional materials, supplies, equipment such as a megaphone, and any permits. For long term initiatives, $1000 may be a good initial goal for materials, permits, professional branding, etc.

Protest costs depend on several factors such as goals, long term strategy, existing capacity among organizers, needed supplies, protest activities, location and environment, and the number of demonstrators. The biggest expenses tend to be around printing and communications as well as providing basic necessities for demonstrators such as food, water, and bathrooms.

Organizers for the Women’s March in 2017, for example, spent $1.6 million for one of the largest protests in history. The main demonstration took place in Washington, DC with around 450,000 participants from around the country. That amounts to $3.50 per participant for a historically significant march on Washington.

Organizers will note, however, that costs do fall on participants (as well as taxpayers) and that some otherwise willing participants may be limited in their participation by financial means. If there are excess funds, issuing travel stipends for participants can be an excellent way to solidify support from activists and create the network needed for long term movements.

Developing Materials & Agenda

Organizers will want to consider what types of materials they will need such as banners and signs. Many items can be made for free with household items, however, some may want to look into professional printing services for larger banners, promotional materials, and other items that may be re-used in the future. The most important point is to have a very clear message that a wide audience will understand. For recommendations on printing and other services, see our Campaign, Materials, and Equipment page.

In some cases, organizers may want to set a rough agenda. Some protest programs may combine actions listed in the above chart. For example, protests may begin as a march and end by picketing. Or, some demonstrations could start as street theater and later turn into a protest. Organizers will want to think through the sequencing of events carefully and be sure they include as many stakeholders as possible in setting and executing the agenda.

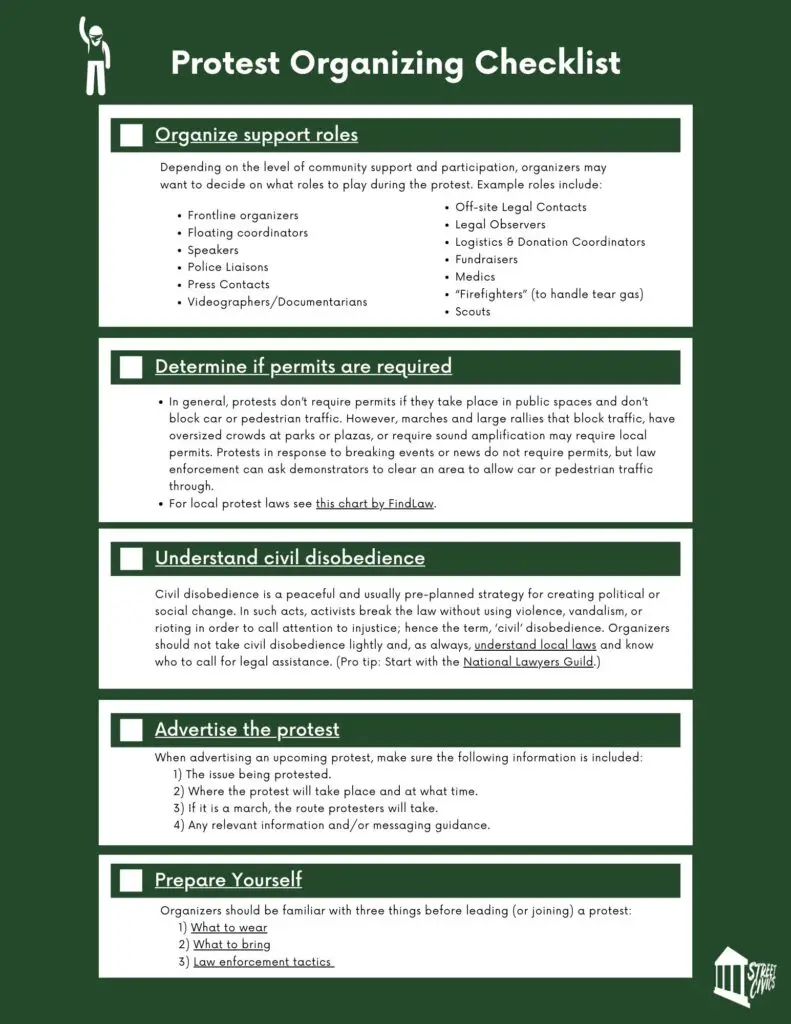

Organizing Support Roles

Depending on the level of community support and participation, organizers may want to decide on what roles to play during the protest. Of course, if numbers are low, some people may have multiple roles; however, some roles require the full attention of a single individual. In some cases, organizers may want to contact professionals who can play helpful supporting roles. Some functions to consider include:

- Frontline organizers serve at the front lines or at the head of a march to help determine how to move the crowd and troubleshoot major obstacles.

- Floating organizers spread out throughout the crowd and should be ready to help answer questions, provide direction, de-escalate tense situations, monitor accessibility for participants and medical personnel, and help keep the crowd calm in cases of emergency.

- Advocacy coordinators can help gather signatures for initiatives, contact information to build lists, and help participants contact elected officials.

- Speakers can be queued up in certain protest situations. If done right, thoughtful speeches that do not go on too long can help build credibility for organizers as well as help energize the crowd.

- Police Liaisons are appointed points of contact for the police. They should introduce themselves to the police in the beginning of the protest and make it clear that they are there to serve as a channel of communication. Police liaisons should not be given any other duty even when things seem quiet as emergencies can arise without notice.

- Press Contacts should start their work before a protest by inviting the press and issuing press releases. During the protest, these activists should look to answer any questions from the press and ensure the press has a safe spot that can capture much of the action.

- Videographers/Documentarians are key to spreading the message of protests, even if the press is on-site. While many participants will be taking pictures and recording anyways, it’s a good idea to have someone who will dedicate their entire participation to filming and edit the clips to make them more ‘shareable.’

- Off-site Legal Contacts should be contacted before a protest. Organizers should have their information with them at all times. I recommend organizers start by contacting the National Lawyers Guild. If they are unable to assist in a particular location, organizers should have the information of a local attorney who specializes in civil liberties.

- Legal Observers are trained professionals that can help monitor the protest for abuses by law enforcement or outside groups. Organizers should seek to contact outside parties for these roles. Again, I recommend starting with the National Lawyers Guild Legal Observer Program. Note that the American Civil Liberties Union has a mobile app called Mobile Justice available on iOS and Android devices to record incidents, access information regarding rights, and request legal assistance.

- Logistics & Donation Coordinators can be useful even during small protests. Having some organizers dedicated to set up, managing equipment, supplies, and donations of items such as water bottles can help provide a backbone for a movement. Organizers should note that these types of arrangements can greatly increase the amount of time protesters are willing to stay. Always, always give careful consideration to bathroom logistics.

- Fundraisers should not be shy to ask for donations from an already supportive crowd. Fundraisers may want to circulate among the crowd or set up a specific tent or stand. Circulating among onlookers is another way to elicit indirect support from sympathetic bystanders.

- Medics are helpful if they are trained in first aid and/or more advanced medical services. They should be clearly marked and should try to stay in a protected yet accessible area, if possible.

- Scouts can help alert organizers and participants when police are lining up for certain tactics such as kettling. Scouts should be familiar with police tactics and should be able to reach a number of organizers over secure lines of communication. Scouts should be posted just outside of the protest area and should attempt to look inconspicuous and unaffiliated with the protest crowd.

- “Firefighters” are a specialty role for activists to help manage tear gas assaults. These individuals should be clothed in the gear such as the below picture illustrates. They can be prepared to use a box, traffic cone, or closed container to cover any tear gas canister; then immediately douse it with water to help saturate the chemical and keep it from dispersing.

Determining if Permits are Required

In general, protests don’t require permits if they take place in public spaces and don’t block car or pedestrian traffic. Marches and large rallies that block traffic, have oversized crowds at parks or plazas, or require sound amplification may require local permits.

Protests in response to breaking events or news do not require permits, but law enforcement can ask demonstrators to clear an area to allow car or pedestrian traffic.

Organizers should note that protests cannot be denied a permit because they are controversial. Additionally, an application fee must have a waiver for those who are unable to afford the fees and permits. Permits cannot restrict desired routes or sound devices for reasons other than public safety concerns or it may violate First Amendment rights. Organizers may want to contact a lawyer or the American Civil Liberties Union if they face difficulties in obtaining a permit or have further questions.

To find local and state protest laws, I suggest referring to FindLaw’s chart here.

Understanding Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is a peaceful and usually pre-planned strategy for creating political or social change. In such acts, activists break the law without using violence, vandalism, or rioting in order to call attention to injustice; hence the term, ‘civil’ disobedience.

These actions can be powerful and have a long history in the United States. Figures such as Henry David Thoreau and Rosa Parks are a few famous examples of individuals that became respected figures for their acts of civil disobedience. The key to some of the more famous success stories was that the activists did not resist arrest and followed the act of civil disobedience with a legal and/or advocacy strategy.

The image of a peaceful protester being arrested for intentionally breaking an unjust law can garner sympathy from the general public. However, civil disobedience should not be taken lightly and organizers should carefully think through the legal and public relations consequences to their actions.

Note that Rosa Parks deliberately broke the law in order to recreate a situation that a 15 year old African American girl, Claudette Colvin, had spontaneously created when she refused to give her seat on a bus to a white person. When considering the legal ramifications of Colvin’s case, Rosa Parks and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) reasoned that the public would not sympathize with a young girl and so recreated Colvin’s arrest with Parks (an older woman who could gain more sympathy from the public).

The fact that the incident involving Parks is so well known today speaks to the careful strategizing that went into the action. Organizers should be aware of the current messaging realities and carefully think through both the message and the messenger.

Organizers, of course, should also be aware of the legal ramifications of civil disobedience. Anyone participating in these activities should assume they will be arrested; therefore, as suggested above, organizers may want to work with outside legal assistance before committing to any acts. (Again, I suggest starting with the National Lawyers Guild.)

While a powerful tool, civil disobedience should not be romanticized too much. These acts, even though peaceful, can turn into violent events if met by force from law enforcement or political opposition. Organizers should be acutely aware that some participants may be more at risk for arrest or violent reprisals than others due to their age, gender, sex, religion, race, ethnicity, or other identifying characteristics. These factors as well as the potential legal fallout (fees, court dates, etc.) should be clearly communicated to participants.

Advertising the Protest

Organizers can learn a lot from the world of marketing both when advertising for a protest and while trying to make their message heard during a protest. Here are some distilled advertising principles for organizers.

When advertising an upcoming protest, make sure the following information is included:

- The issue being protested.

- Where the protest will take place and at what time.

- If it is a march, the route protesters will take.

- Any relevant information and/or messaging guidance.

- Note: organizers may want to remind participants to make sure any signage has clear messages that would be understandable for bystanders with little or no knowledge of the situation. Avoiding acronyms, obscure references, and other confusing messages can be key in building public support.

To advertise a protest, organizers can consider the following methods:

- Posting flyers,

- Handing out leaflets,

- Canvassing on the street or door-to-door,

- Texting and direct messaging supporters,

- Making announcements at church groups, community gatherings, etc.,

- Notifying email lists and online forums,

- Making a public service announcement on the radio,

- Posting promotional material to social media, websites, and other online platforms.

Movement Strategies

When planning a protest, organizers should also have in mind a long term political or social change strategy. Mapping out such a strategy can be difficult in the beginning, but it is vital to success in the long-term. In the short-term, having an idea of where the movement is headed can help shape current activities.

For example, if a movement plans to use economic means in their strategy, organizers could start by picketing and, later if demands go unmet, they could escalate their tactics to a boycott.

Previously on this site, I wrote about seven fundamental strategies for grassroots movements to give organizers an idea of common approaches. In practice, of course, these strategies can bleed into one another and don’t necessarily represent the entire spectrum of possibilities. They are useful guideposts, however. Below is a quick reference chart of the seven strategies.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Policy Change and Advocacy Strategies | Policy change strategies are the most common ways to harness the power of grassroots. This strategy is defined by deliberate pressure on elected leaders and officials to change policies. Often, groups using this approach focus on Congress by asking for things like a new law to be enacted, an existing law to be changed, or to stop a proposal from becoming law. |

| Nonviolent Action & Civil Disobedience | While policy change and advocacy may be the most common grassroots strategy, nonviolent action and civil disobedience are likely what most people picture when they think of the “grassroots movements.” The approach uses public displays of opinion such as rallies or acts that deliberately (and nonviolently) break the law like hunger strikes. |

Challenges to Legal Authority and Legitimacy | Challenges to legal authority could also be thought of as advocacy through the courts and the court of public opinion. This strategy challenges the legitimacy of laws, policies, or institutions through legal arguments, lawsuits, and public messaging. While this approach requires the help of attorneys, grassroots movements have been able to utilize this strategy more broadly to help spur social change. |

| Political Resistance | Political resistance is a deliberate attempt to nonviolently sabotage or disrupt a government or occupying power. In its most pure form, it is typically reserved for extreme moments in history such as the Nazi occupations during World War II. However, the approach has appeared in times of relative calm as well and can be seen in isolated acts throughout history. |

| Social Transformation Models | Social transformation models attempt to change societies by first shifting individual beliefs and behaviors and, from there, building toward social and political reform. This approach usually applies other grassroots strategies in a sequence over time to transform society from the bottom up. |

| Economic Means and Leveraging | Movements that use economic means and leveraging seek to change institutions by either building a stigma around certain transactions and/or by draining an institution of resources. The strategy uses tactics like boycotts, strikes, and divestment campaigns to alter established policies and/or practices. |

| Citizen Action and Empowerment | Citizen action and empowerment is a broad category of grassroots strategy that seeks to provide services, protections, and development directly to the community. This strategy differs from other approaches to grassroots activism in that it does not necessarily seek to alter policies or laws but, instead, fill gaps in social services left by the government. |

Most Effective Protest Methods

The most effective protest methods are nonviolent, adaptable to changing events, directed toward specific demands, engaging for protesters, appeal to mass participation, and help encourage defections from opposing political camps.

Research and commentary on the most effective nonviolent movements have largely examined characteristics of successful movements (e.g. violent vs nonviolent) as opposed to on-the-ground actions (e.g. picketing vs marching). So, organizers should feel free to take license with their actions so long as they adhere to the principles outlined above and avoid violence and vandalism.

The principles are distilled from the research of Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan and their book Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (available via our Amazon affiliate link here) as well as the analysis of Greg Satell and Srdja Popovic.

One of the most important aspects organizers should keep in mind is that the more participation a movement can get, the more effective it will be. Chenoweth and Stephan examined 323 cases of civil unrest from 1900 to 2006 and found that movements with low participation barriers were more successful. In practice, this meant that nonviolent movements were twice as successful as violent insurgencies because they attracted more participation.

Chenoweth and Stephan also found that defections from opposing political camps, the military, or the regime in power were a tell-tale sign that a movement had a good chance at success. What this means for organizers is that tactics need to attempt to win over the opposition and not crush it.

Satell and Popovic illustrate the need to win over opponents in their analysis of the successful protests against Slobodan Milošević in Serbia during the late 1990s. The demonstrations were organized by a group called Otpor which (among other things) trained activists to protect police from any violence instigated by demonstrators. Organizers also saw arrests as opportunities to build relationships with the police and plant the seeds of defection.

Another factor organizers may want to keep in mind is how to build an identity for the movement. Many successful nonviolent movements had distinctive qualities such as the Candlelight Revolution in South Korea or the Singing Revolution in the Baltic states. Acts of solidarity like lighting a candle or signing are exactly the type of activity that can invite wider participation and increase the chances of success.

Turning Protests into Political Change

In some cases, protesting may be the only path to political change available for activists in which case organizers will need to remain persistent. If other means of political change are available, they should seek to diversify their tactics and strategies so that the protests are effectively leveraged.

Regardless of the pathways available, protesters should remain focused on clear demands and clear communication of those demands.

Organizers should also have a clear idea of what they will do if and when they succeed. If a movement is pushing for significant political change, protesters should develop a very clear plan of how to implement reforms. Some revolutions have succeeded at toppling governments, but have failed to produce long term change because there was no clear plan for structural reform.

Below is a list of recommended reading for means of political change that organizers can employ to leverage and compliment their protesting.

- 31 Effective Strategies & Methods That Advocates REALLY Use

- 7 Classic Examples of Advocacy

- Seven Fundamental Strategies for Grassroots Movements

- Community Organizing Basics: Power, Interests & Saul Alinsky

- 9 Textbook Examples Of Grassroots Activism

- What Does It Mean To Advocate? (3 Things To Know)

- A Protester’s Field Guide to Effective Action (companion piece to this article)

Recent Posts

Writing a letter to the president can be an effective way for advocates to have their voices heard, influence policy decisions, and move public opinion if done with some planning and intentionality....

This is a user-friendly guide to effective protesting. Topics include individual involvement, what to know before joining a protest, what to wear, on-the-ground tactics, encounters with law...