Digital and online platforms have become an important tool for advocates, activists, and organizers all over the world. So, it’s important to start with a basic definition.

Social media advocacy means to advance social causes and/or policy recommendations through public education and lobbying over social media sites. Ultimately, advocates seek social and/or institutional change by moving public opinion and persuading policymakers.

Note the terms “digital advocacy” and “social media advocacy” mean much the same thing – though, digital advocacy can be broader and inclusive of other online tools. For the purposes of this post, I’ll use the terms interchangeably, though.

Below, is a look at strategies, tips, and warnings for social media advocates. The focus remains on how to move public opinion and persuade policymakers rather than offering specifics on which platforms and features to use. If you’re interested in setting up digital advocacy campaigns check out our resource page for more.

First, Keep in Mind These Three Things…

There are three major aspects of social media that advocates should keep in mind before diving into strategy. They are:

1. How people use social media platforms is constantly changing.

Social media is still a very new phenomenon and it will likely continue to evolve in many ways. In the first decades of its existence, social media saw a dramatic rise in popularity.

Along with this rise in popularity, the fundamental nature of the platforms seemed to change as well. For example, over ten years in the U.S. social media sites went from largely being a youth phenomenon for socializing to becoming an important channel for civic engagement among most adults.

Worth noting is that some trends that were true at the start of social media may always remain true. Platforms that are popular today could fall out of use in the years to come. And, new features and algorithms will perpetually create new content and ways to engage, thus changing users’ relationship with the sites.

While social media is associated with a fast-paced world, the platforms ultimately only move as fast as humans. Fundamental shifts in how people engage with social media – like building trust – can take years to play out.

So, advocates should not necessarily feel the need to be on top of every minor fad. While generally staying on top of the latest trends is important, advocates should spend more time devoted to thinking about long term strategy as well as staying consistently engaged and on message.

2. EVERY Community Has A Different Relationship With Social Media.

While it’s easy to think of cyberspace as being the same everywhere, studies have clearly shown that social media engagement varies greatly from country to country and even city to city.

In the wake of the Arab Spring, for example, many scholars argued that social media was behind these seemingly spontaneous revolutions across the Middle East. The truth, however, was much more complex and social media played very different roles in different countries.

In many cases, the role of social media was likely exaggerated because it was such a visible feature of the events. In many locations, social media was only available to a small percentage of “elites” and not necessarily the majority of protestors.

Generally, advocates should look at the latest poll data and academic research (if available) to understand how their community engages with social media. Having a handle on how much trust your community has for social media and how political bias shapes people’s online behaviors can give you a strong leg up when pushing for social change.

3. Social Media Is ONE Tool Among Many.

It’s easy to get caught up in the social media treadmill, but recognize that online platforms can only take a movement so far. While it is possible for change to be sparked by social media alone these days, advocates should not depend on it.

Further, any movement that relies on a single mode of communication is highly vulnerable. The more ways that a network of activists and organizers communicate – the better. Social media censorship and government shutdowns have been increasing throughout the world in recent years, specifically to suppress political dissent. That means that advocates need to build in-person networks the old fashioned way too.

Good organizers know that movements stand the best chance of success when they start with people to people engagement – not “friending” – and rely on personal relationships – not followers.

Strategies

Know Who To Target

Social media engagement has been found to create trust between citizens and their government. However, advocacy necessarily means championing positions that the current government opposes or has not implemented. Therefore, advocates (as opposed to ordinary citizens) may find that building trust with policymakers over social media is difficult.

Advocates will be quickly dismissed if they spam officials with social media posts. If policymakers or their staff come to know an advocate on social media, their online reputation will follow them into meetings. So, consider tactful and light engagement with policymakers on social media.

Keep in mind though, persuading those in power will likely require in-person engagement and grassroots support.

The real power of social media is in its ability to reach new audiences and serve as a public education platform. Social media, however, is not usually the best platform to engage the opposition. Often, these types of engagements are a psychological and emotional drain, and chances of converting opponents are low (though not unheard of). If you’re seriously considering reaching out to opponents, try the old-fashioned way.

Know How To Target

Knowing how to “go viral” is the holy grail of social media. While there is no magic formula to get your post to go viral, there are some clear tactics to keep in mind. Notably, advocates for social and political causes are automatically in a strong position to go viral due to the type of content they share most often.

To understand what type of content goes viral, we turn to the internet marketing geniuses at Outgrow who created this infographic.

Contextualize The Message

As discussed above, every community has a different relationship with social media. Issues can arise, however, when messages are lifted out of local contexts. One message may be empowering when amplified by the right communities (which can add context and nuance) while damaging if amplified by others (which may gloss over details or drown out local voices).

Advocacy campaigns have always been subject to figurative hijackings by other actors as well – even before social media. However, the platforms have made it easier than ever for outside forces to appropriate a campaign’s messaging, manipulate it, and/or misrepresent it. This happens sometimes despite the best of intentions. Even the most beloved charities and celebrities have participated in questionable campaigns or good campaigns but in questionable ways.

This is important for advocates to keep in mind for two reasons:

- The more successful a campaign becomes, the less control over messaging an advocate has. It’s not uncommon for original voices to be drowned out at the later stages of a campaign when higher-profile individuals and organizations lend support. Advocates should remember to communicate clearly to recruits the intentions for the campaign. Spelling out from the very beginning whose voices needed to be centered and how new champions can play supportive roles is a good way to give a campaign some integrity.

- Understand the context of a campaign before lending support. Often advocates lend support to campaigns in other communities or on issues that don’t directly impact them. That’s great – so long as advocates have a very thorough understanding of the context and how they can be most helpful. It’s not uncommon for do-gooders to take up a cause without getting the full story and actually doing harm in the process. The textbook example of this scenario is the Kony 2012 campaign, which I encourage every social media advocate to review.

Be In It For The Long Haul

As stated above, fundamental shifts in human behavior take time and, even though social media moves our messages faster and farther than ever, advocates need to have a long term mindset. Campaigns can take years, decades, or more to come to fruition.

One of the most successful digital advocacy campaigns to date – the #MeToo movement – took upwards of a decade to gain public traction. For years, Tarana Burke chipped away at a public education campaign until one day – a celebratory (Alyssa Milano) amplified her message. After that, the movement reached tens of millions of supporters around the world practically overnight – that is, after ten years of hard work.

Throughout a campaign, social media trends may come and go, platforms may rise and fall, but with a long term view towards change, this should not threaten a well-planned and persistent campaign. Note that the #MeToo movement started on MySpace!

Tips

The Periphery Is Your Friend

Social media research has revealed some fascinating aspects of how people share and consume information as well as how networks of individuals behave. Notably, researchers have found that political information networks differ from all other information networks (like those sharing entertainment news).

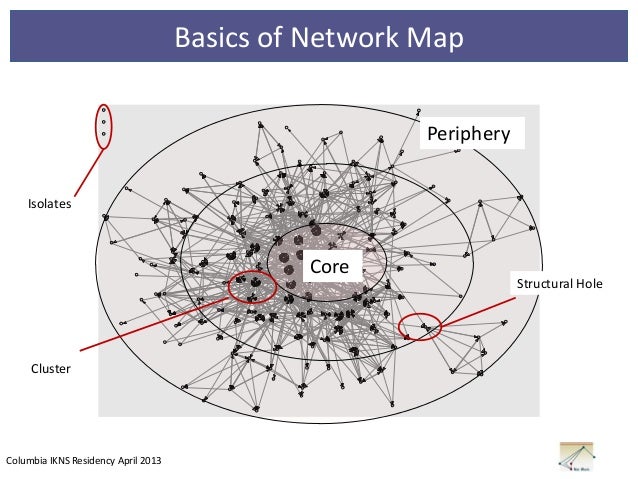

For information networks, there are typically two roles participants can play (though, it can also be thought of as a spectrum). Either network members are part of the “core” or the “periphery.” The core consists of those who produce the information and are sometimes the object of the news themselves. The periphery may not be directly connected to the content or issue but still participates in sharing the information.

In political networks like advocacy campaigns, the core is responsible for not just generating information (which could come in the form of opinions), but the core also sustains the activity around the information (i.e. commenting, posting, etc). The periphery only participates in activity occasionally and to varying degrees.

This contrasts with how entertainment news travels through networks, for example. In these networks, the core produces the information but the periphery sustains the conversation. In other words, the fans talk more about celebrity gossip than celebrities do.

These insights have at least two important implications for advocates:

- In the early stages of a campaign, advocates need to concentrate on building a solid core of allies. There must be a tight-knit group of advocates that trust and amplify one another at the center of every campaign. Things really can’t get rolling on social media or elsewhere until there is a core for the campaign.

- The periphery are reinforcements – not “posers” or “slacktivists.” Even the most seasoned activists can roll their eyes when everyone starts to hop on the bandwagon. Yet, this is the goal. As stated above, advocates often work hard for many years until a breakthrough occurs. The problem is that when that breakthrough occurs, there may be some resentment among those in the core (who worked for years) for those in the periphery (who joined only for a moment).

When those who were previously uninvolved suddenly join a campaign enthusiastically, advocates should work hard to try to convert some of the recruits into core membership. The boon in participation won’t last forever and each core member has a compounding effect.

Beware Of The Block!

An increasing trend among politicians is to block social media users with whom they disagree or dislike. While this act has been declared unconstitutional in the U.S., enforcement has been slow and many politicians have not yet complied. Elsewhere in the world, the phenomenon has been growing as well.

Advocates who continuously engage officials over social media should be aware that they may get blocked regardless of the legality. In some cases, advocates have turned the act of being blocked into an issue itself to demonstrate the inaccessibility of politicians.

When planning advocates should be familiar with local laws regarding officials on social media and consider carefully what, if anything, a block from an official would mean for the campaign.

Worth noting here is that the ease with which users can be blocked on social media means that in-person organizing tactics won’t work if tried exclusively online. Some basic organizing theory suggests that isolating a political target can be effective in getting concessions. This tactic is still effective, but cannot be carried out through social media alone.

Warnings

Government Surveillance And Targeting

If you’re on social media, it is safe to assume you are being watched by at least one government (likely your own and/or the U.S. government). If you’re running a political or issue campaign you may be watched by multiple governments regardless of the issue.

Social media is a prime starting point for surveillance. Leaked training documents for one of the most sophisticated surveillance systems known to man – XKeyScore – revealed that U.S. intelligence agencies were taught to “start with social media.” No doubt, that social media is where the low tech forms of surveillance start too.

For advocates, this can mean a few things. Government or independent actors may be harvesting data en mass where every post is just a needle in a haystack. Or, these groups may specifically target advocates to monitor and suppress dissent. In other cases, foreign governments or independent organizations may monitor and manipulate online political discussions to sow discontent.

All of these scenarios play out daily. Most seasoned advocates will have experience or, at least be familiar, with the idea of government actors infiltrating activist networks to disrupt movements. This happens on a larger and faster scale over social media and many governments are employing bots to do much of this work for them.

Advocates should be intimately familiar with the risks posed by their work. Even if an issue seems apolitical, it may make advocates a target for harassment and/or the campaign a target for hijacking. Staying vigilant, maintaining discipline over campaign content, and making sure recruits are who they say they are can help hedge against uninvited participants in your campaign.

Harassment

Online harassment (or “cyberbullying”) is a well-known phenomenon. When it comes to carrying out political or issue campaigns over social media, advocates should anticipate some harassment. The amount and type of harassment advocates face depends on many circumstances, but gender appears to be a primary factor. (Note that much research remains to be done in this field including areas such as the experiences of transgender politicians and advocates.)

Men

Research has shown that men, on average, receive more political harassment than women. However, this does change at different levels of notoriety. For example, a lesser-known male politician will receive more harassment on average than a female politician of the same status. This reverses for politicians with high public profiles; a high-profile female politician will receive more harassment than her male counterpart.

For advocates, this trend is likely similar to politicians. Therefore, male advocates should expect some harassment even when relatively unknown.

Women

While men experience more political harassment on average than women, women receive much higher rates of gender-based harassment. Women also tend to receive more aggressive and threatening treatment from online harassers.

Women politicians across the world have documented particularly disturbing threats that were often personal in nature and threatened their safety or the safety of their loved ones.

These trends are likely similar among female advocates. Female advocates, then, should prepare themselves for potential harassment and develop reliable networks for emotional support – ideally with timely check-ins on physical whereabouts and safety.

Harassment As Political Resistance

Regardless of gender, much of the political harassment that politicians and advocates face online is likely an expression of political resistance. The intent is to irritate and undermine the opposition psychologically and to divert time and energy.

Harassment may or may not be organized by an individual or group; a good portion of it may arise from impassioned supporters acting on their own (though more research is needed). Much of the provocations are likely empty words, but politicians and advocates should use their best judgment when assessing the threat harassment poses.

Understanding that harassers are trying to sap energy from politicians and advocates can put some of the attacks in perspective. For the low-risk harassment, much of it is meant to take advocates or politicians off task; simply being aware of this can help in dealing with the psychological effects. Staying focused on regular work and not dwelling on these types of messages is the best way to mollify political resistance strategies.

Final Word

While some of the information above regarding surveillance and harassment may sound drastic, there are two reasons I’ve included this information – 1) the warnings above are based on the experiences by tens of millions of people, yet they are rarely found in similar posts about social media campaigns, and 2) advocates can better handle these things if they prepare for them.

These warnings, though, should not deter anyone from raising their voice. After all, surveillance and harassment may be incidental to a campaign and some advocates may never experience serious forms of it. Others may experience heavy harassment and surveillance. In these cases, having a forewarning can take some of the shock out of the discovery.

If you’re serious about digital and social media advocacy, I encourage you to check out these additional resources:

- Digital Communications & Software resource page

- The Impact of Social Media on Politics

- Political Campaigns on Social Media (Notes from My Research)

Recent Posts

Writing a letter to the president can be an effective way for advocates to have their voices heard, influence policy decisions, and move public opinion if done with some planning and intentionality....

This is a straightforward guide for organizers who are planning protests. The below sections layout the logistics of organizing a demonstration, strategies, and tactics, and how to leverage the event...